GUEST CURATOR: Anna MacLean

What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

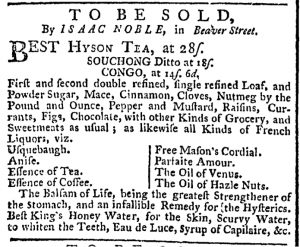

“TO BE SOLD … BEST HYSON TEA.”

An advertisement in the April 18, 1768, issue of the New-York Gazette: Or, the Weekly Post-Boy announced “BEST HYSON TEA” in addition to “Mustard, Raisins, Currants, Figs, Chocolate, with other Kinds of Grocery.” I felt compelled to select this advertisement because it sounds absurd to conceptualize a time when America didn’t “run on Dunkin’” coffee (a testament to marketing in modern America). However, by similar means, tea drinkers in colonial America looked forward to the caffeine buzz found in their kettles and teacups.

Hyson tea, characterized by Oliver Pluff & Co. as having a long twisted appearance, was a favorite among American colonists. According to the Boston Tea Party Ship and Museum, during the first half of the eighteenth-century tea was a costly luxury that only a small percentage of the colonies’ population could afford. By the middle of the century, tea was in high demand throughout the colonies and costs decreased making it an everyday beverage for the vast majority. Over time, the American colonies had evolved into a province of tea drinkers.

Yet drinking tea was far more than a hobby in colonial America but rather an “instrument of sociability,” according to the review of Rodris Roth’s “Tea Drinking in 18th-Century America” on Colonial Quills. An invitation to drink tea was an invitation to a social event, perhaps a small, informal gathering or maybe an elegant dinner party.

**********

ADDITIONAL COMMENTARY: Carl Robert Keyes

In addition to the “other Kinds of Grocery” that he sold at his shop on Beaver Street in New York, Isaac Noble also advertised “all Kinds of French Liquors” and listed eight varieties. Since Anna chose to examine one of Noble’s wares that remains popular today (even if it has not retained the cultural currency it enjoyed in eighteenth-century America), I decided to take a closer look at some of these other beverages that colonial Americans drank but that might be less familiar to consumers today.

The Oxford English Dictionarydescribes “Parfaite Amour” as “a sweet liqueur of Dutch origin, flavoured with lemon, cloves, cinnamon, and coriander, and coloured red or purple.” In addition to the taste, colonists may have been entertained by the color! Several other items on Noble’s list appear to have been liqueurs as well, including “Anise,” “Essence of Tea,” “Essence of Coffee,” and “Oil of Hazle Nuts.” While it may be fairly easy to imagine the flavor and composition of each of those “French Liquors,” the “Oil of Venus” presents more of a challenge. One Household Encyclopedia published in the middle of the nineteenth century includes recipes for both Oil of Jupiter and Oil of Venus. It describes Oil of Venus as brandy infused with caraway, anise, mace, and orange rinds and mixed with sugar. Published nearly a century after Noble’s advertisement appeared in the New-York Gazette: Or, the Weekly Post-Boy, that recipe may not have been the same as the “Oil of Venus” colonists drank, but the mixture of spices does appear consistent with methods for distilling the “Parfaite Amour” listed immediately before it. The nature of the “Free Mason’s Cordial” remains more elusive, but it turns out that the “Usquebaugh” was not as exotic as the name might suggest. The Oxford English Dictionary indicates “usquebaugh” is an Irish and Scottis Gaelic word for whisky. Like tea, usquebaugh/whisky remains a popular beverage today, even if the average person does not consume either in the same quantities as colonists did in the eighteenth century.

The various “Kinds of French Liquors” advertised by Noble may not seem readily identifiable to twenty-first-century consumers, at least not by the names used to describe them in the eighteenth century, but several continue to be sold and consumed today. As a result of advances in marketing practices, some are now better known by specific brand names rather than the general descriptions deployed in the colonial era.