What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“A COMPLEAT and CORRECT MAP of SOUTH-CAROLINA.”

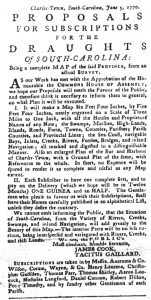

In the fall of 1773, James Cook, a surveyor, advertised a “COMPLEAT and CORRECT MAP of SOUTH-CAROLINA” to readers of the South-Carolina Gazette and Country Journal. He underscored that he went to “great Expence in surveying” the colony, “informing himself of the District Lines, Sea-Coast, &c. with many other Particulars of general Utility.” Furthermore, he made arrangements for “the Engraving and Colouring [to be] executed by the best Hands in London.” The surveyor asserted that his map was “as useful a Piece of Geography as any extant. According to William P. Cumming in British Maps of Colonial America, as quoted in the overview presented by David Rumsey Map Collection, Cook’s map was “the most detailed and accurate printed map of South Carolina, especially for the interior, yet to appear.” You may examine a high-resolution image of Cook’s “Map of the PROVINCE of SOUTH CAROLINA” at the David Rumsey Map Collection.

In his advertisement, Cook declared that map provided “a clear Idea, not only of this Province, but of the Catabaw Nation, Part of North-Carolina, and as far back as the Blue Mountains, … together with the established Dividing Line of the two Provinces.” A small amount of territory denoted “CATABAW NATION” appeared in the northern region, but the depiction of “Catabaw Town” consisted of six squares, presumably representing houses. The insets provided more detail of English settlements and outposts: “A PLAN of CHARLESTOWN,” “A PLAN of GEORGETOWN,” “A PLAN of CAMDEN,” “A PLAN OF BEAUFORT ON PORT ROYAL ISLAND,” and “A DRAUGHT of PORT ROYAL HARBOUR in SOUTH CAROLINA with the Marks for going in.” Mapping the colony from the coast into the interior was an act of taking possession of the land (including, as the title of the map stated, “Roads, Marshes, Ferrys, Bridges, Swamps, Parishes Churches, Towns, Townships; COUNTY PARISH DISTRICT and PROVINCIAL LINES) and waterways (including Rivers, Creeks, Bays, Inletts, Islands [to facilitate] INLAND NAVIGATION”). That simultaneously dispossessed indigenous inhabitants or, in the case of the Catawba, confined them to small districts. One more inset depicted a scene with two well-dressed English gentlemen, either merchants or planters, conversing next to the cargo of a ship with several buildings visible on the other side of a harbor or river. An enslaved African, shirtless in contrast to the finery of the gentlemen, carries a parcel on his back. An indigenous man observes, sitting on the other side of a tree and an alligator, removed from the English settlement and the commerce undertaken by the English gentlemen and the enslaved African. He holds a bow in one hand and an arrow in the other, representing, from the perspective of the producers and consumers of the map, the dangers that colonizers continued to face from the indigenous population.

Cook hoped that the map “will merit the Approbation of the Public” and sell many copies “at the low Price of TWO DOLLARS and a HALF.” Whatever the sales may have been in the 1770s, only six copies survive, five in institutions in the United States and a sixth at the British Museum. Perhaps so few survive in part because consumers did not purchase the maps solely to decorate homes or merchants’ offices but instead used them to traverse the land and waterways of the colony.