Who were the subjects of advertisements in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

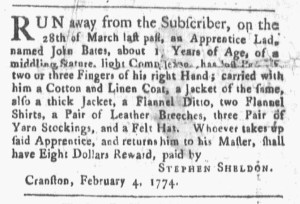

“RUN away … an Apprentice Lad, named John Bates.”

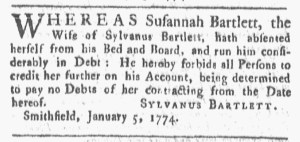

“Susannah Bartlett, the Wife of Sylvanus Bartlett, hath absented herself.”

“RUN away … a Servant Man, named Kimbal Ramsdill, a pretended Carpenter or Joiner.”

Colonizers used various kinds of “runaway” advertisements in their efforts to maintain social order. Such was the case in the February 5, 1774, edition of the Providence Gazette. Several colonizers published stories of subordinates who ran away, giving directions about how others should interact with them if they happened to encounter them.

In the first of those advertisements that readers saw if they perused the newspaper from the first page to the last, Stephen Sheldon of Cranston announced, “RUN away … an Apprentice Lad, named John Bates.” The apprentice had departed on March 28, 1773, nearly a year earlier, but Sheldon hoped that his advertisement would result in recovering him. He offered “Eight Dollars Reward” to “Whoever takes up said Apprentice, and returns him to his Master.” He also provided a physical description to aid in identifying the runaway, including an especially distinctive feature. The young man “has lost two or three Fingers on his right Hand.”

The next advertisement revealed marital discord in the Bartlett household in Smithfield. “Susannah Bartlett, the Wife of Sylvanus Bartlett,” the husband proclaimed, “hath absented herself from his Bed and Board, and run him considerably in Debt.” Accordingly, he no longer assumed responsibility for her expenses. Invoking language that appeared in such advertisements throughout the colonies, Sylvanus declared that he “hereby forbids all Persons to credit her further on his Account, being determined to pay no Debts of her contracting.” As had been the case with Sheldon running an advertisement about Bates, Sylvanus had much greater access to the public prints than Susannah, so readers of the Providence Gazette knew only one side of the story. The apprentice and the wife may have had good reasons to leave the Sheldon and Bartlett households.

In another advertisement, Benjamin Cargill of Pomfret, Connecticut, described Kimbal Ramsdill, a “Servant Man” and a “Pretended Carpenter or Joiner” who had “RUN away” the previous December. Cargill indicated that Ramsdill often misrepresented himself, not only in terms of his trade but also his origins. “The above Fellow,” he stated in a nota bene, “pretends at Times he was born at Lynn, and at other Times at Newbury.” Indeed, he was “much given to Lying, and apt to tell of his having Land in different Parts.” In this instance, Cargill did not ask readers to accept his word alone that Ramsdill engaged in unsavory behavior. He reported that the indentured servant “hath lately been convicted of Stealing, and publicly whipped seven Lashes, the Marks of which perhaps may yet be seen.” Cargill promised “Ten Dollars Reward” to “Whoever will take up said Servant, and secure him in any of his Majesty’s Goals [Jails].”

The advertisements in the Providence Gazette and other colonial newspapers did not merely market goods and services to consumers. Many of them instead delivered news about local events, including cases of runaway apprentices, wives, and indentured servants. The colonizers who placed those advertisements did so for their own purposes, but also thought they did the community a service by warning about men and women who did not abide by behavior considered appropriate to their status or, sometimes, had even been convicted of crimes. While there are many reasons not to lump John Bates, Susannah Bartlett, and Kimbal Ramsfill together, the men who placed advertisements about them belonged to a common category of colonizers who used the power of the press in their efforts to impose order on subordinates who they reported had misbehaved.