What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“He has had the Pleasure of pleasing some of the most respectable Gentlemen in London.”

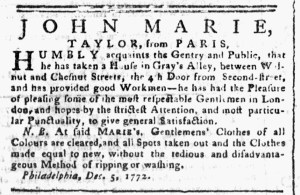

John Marie, a tailor, wanted the better sort to know that he was well qualified to serve them at the shop he ran out of his house in Gray’s Alley in Philadelphia. In an advertisement in the December 12, 1772, edition of the Pennsylvania Chronicle, he introduced himself as a “TAYLOR, from PARIS.” He intended that his connection to one of the most cosmopolitan cities in Europe, a city where the fashionable often set tastes adopted in London, the most cosmopolitan city in the British Empire, would recommend him to genteel consumers in the largest and one of the most cosmopolitan cities in the colonies. He made clear that he sought a particular kind of client by addressing “the Gentry and Public.” Consumers and tailor would mutually benefit from their association as Marie enhanced the appearances of his clients and those clients gained the cachet of being dressed by a French tailor.

To demonstrate that he was prepared to work with the local gentry, Marie heralded his previous experience. The tailor proclaimed that he “has had the Pleasure of pleasing some of the most respectable Gentlemen in London,” though he was too discreet to mention names. That he served “respectable Gentlemen” suggested that he kept them outfitted according to the latest styles but did not resort to anything too frivolous or outrageous. Prospective clients could depend on him dressing them well without transforming them into the macaronis who were the target of so much derision in both London and Philadelphia in the 1770s. In “Fashion and the Culture Wars of Revolutionary Philadelphia,” Kate Haulman explains that the term macaroni “applied to elaborately powdered, ruffled, and corseted men of fashion” whose “suits were opulent and closely cut, with incredibly slim silhouettes.”[1] A series of prints published in London depicted all sorts of men, “from farmers to barristers,” as macaronis. Thus, Haulman argues, “macaroni could apply to any man who followed fashion to ape high status.”[2] Marie suggested that he did not seek to serve such pretenders. The gentry in Philadelphia could depend on him to dress them as “respectable Gentlemen,” just as he had done for his clients in London.

[1] Kate Haulman, “Fashion and the Culture Wars of Revolutionary Philadelphia,” William and Mary Quarterly, 3rd ser., 62, no. 4 (October 2005): 635