What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago this week?

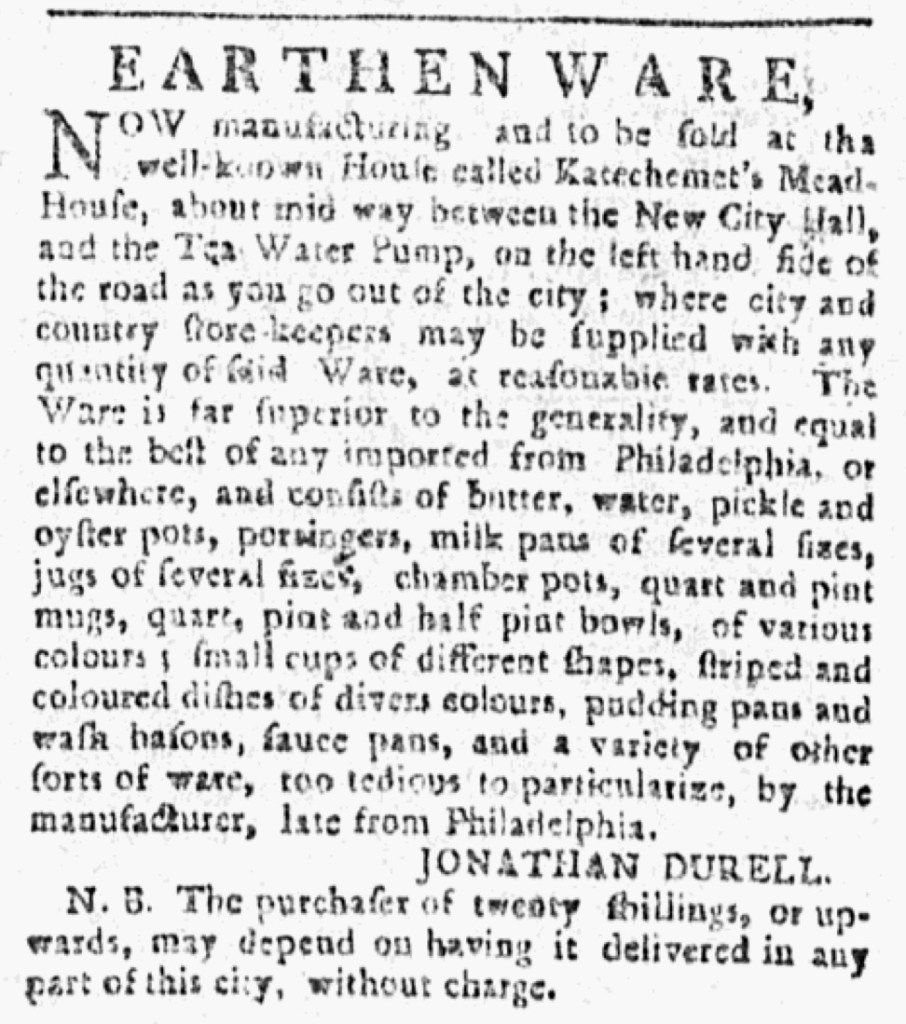

“EARTHENWARE … equal to the best of any imported from Philadelphia, or elsewhere.”

As fall arrived in 1775, Jonathan Durell took to the pages of the New-York Journal to advertised “EARTHENWARE” that he made locally and sold “at the well-known House called Katechemet’s Mead-House” on the outskirts of the city. The potter offered a variety of items, including, “butter, water, pickle and oyster pots, porringers, milk pans of several sizes, jugs of several sizes, chamber pots,” and “a variety of other sorts of ware, too tedious to particularize.” Durrel promoted these items as “far superior to the generality, and equal to the best of any imported from Philadelphia, or elsewhere.” He also reported that he had migrated to New York from Philadelphia.

Mentioning Philadelphia twice in his advertisement was intentional. When Durell compared the quality of his earthenware to items imported into New York, he did not refer only to goods arriving from English manufactories, though looking to alternatives would have been on the minds of consumers while the Continental Association remained in effect. Colonizers who wished to purchase “domestic manufactures” in support of their political principles knew that Philadelphia was an important center for pottery production. Deborah Miller, an archaeologist, notes that Philadelphia Style earthenware “became recognized across the colonies for its quality and durability” by the middle of the eighteenth century. Citing Durell’s advertisement, Edwin Atlee Barber states that “it would appear that even before the Revolution the wares made in Philadelphia had acquired a reputation abroad for excellence.”[1] Durell’s pottery was not made in Philadelphia, but he had resided there and presumably used the same techniques to produce his earthenware. As both consumers and “city and country store-keepers” sought goods made in the colonies, he presented an attractive option.

To increase his chances of making sales, Durell mentioned the “reasonable rates” he charged for his earthenware and provided a convenient service. In a nota bene, he declared, “The purchaser of twenty shillings, or upwards, may depend on having it delivered in any part of this city, without charge.” The potter hoped that free delivery would entice customers to take a chance on earthenware that he asserted matched any others, including products from Philadelphia, in its quality.

**********

[1] Edwin Atlee Barber, The Pottery and Porcelain of the United States: An Historical Review of American Ceramic Art from the Earliest Times to the Present Day (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1893).