What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“WHEREAS I the Subscriber signed an Address to the late Governor Hutchinson — I wish the devil had had said Address before I had seen it.”

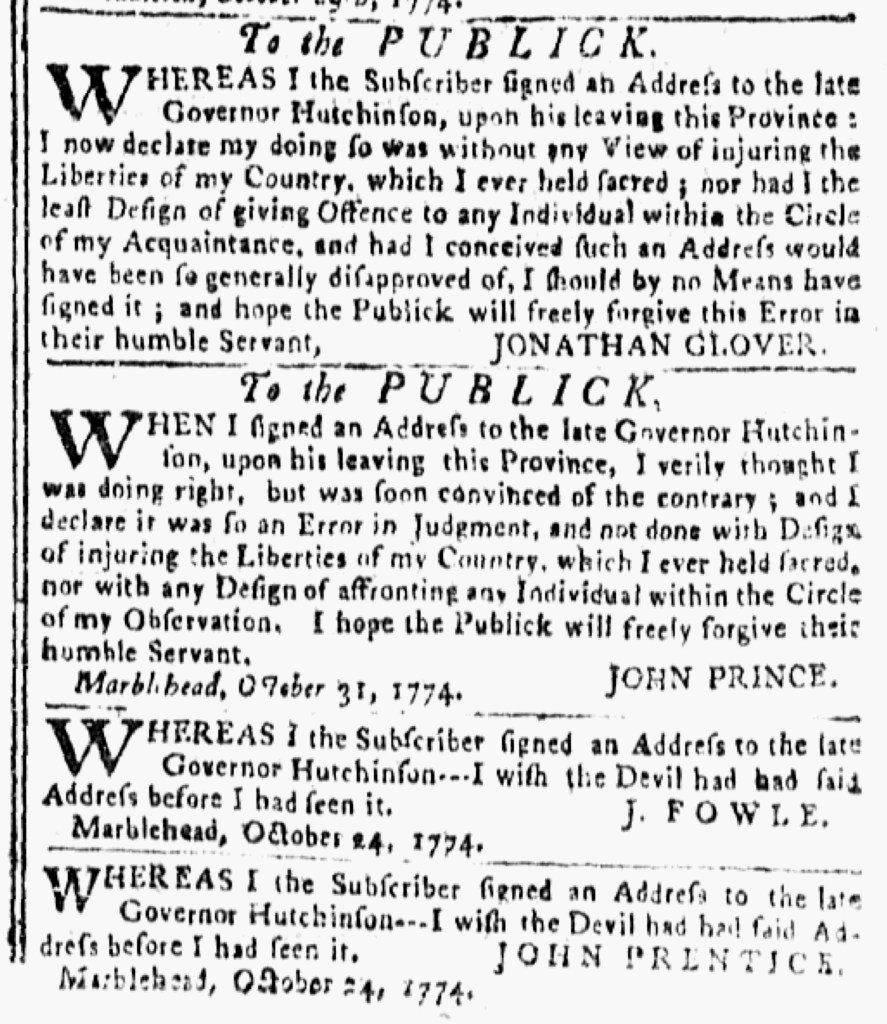

More advertisements from men who wished to recant after signing “an Address to the late Governor Hutchinson, upon his leaving the Province” appeared in the November 1, 1774, edition of the Essex Gazette. John Stimpson’s letter to that effect ran as an advertisement a week earlier, joined now by letters from Jonathan Glover, John Prince, J. Fowle, and John Prentice. The printers, Samuel Hall and Ebenezer Hall, positioned them one after another at the end of a column, following an advertisement about a stray cow. Their position on the page indicated that the Halls considered these letters to be advertisements. In that case, they would have charged to run them in their newspaper.

Other printers, however, treated some of these same letters differently. The short missives from Fowle and Prentice each appeared in the Boston Evening-Post, the Boston-Gazette, and the Massachusetts Gazette and Boston Post-Boy the previous day. In two of those newspapers, they ran with local news, while in the Boston-Gazette the printers placed them between news and advertisements. They could have been the final news items or the first advertisements in that column. Even if the printers considered them advertisements, they delivered news to readers.

In the Boston Evening-Post, Thomas Fleet and John Fleet, the printers, provided commentary, reporting that they “have received the Declarations and Acknowledgments of several Deputy Sheriffs, and other Persons, who by signing an Address to Governor Hutchinson had rendered themselves obnoxious to the People.” They did not have room to publish all of them in that issue, but considered two of them “so concise we can’t omit obliging our Readers with them, as they may serve for a Specimen to other Addressers whose Principles are such as not to incline them to make long Confessions, even when they know they were to blame.” Samuel Flagg had offered one of those “long Confessions” in the Essex Gazette a month earlier.

Fowle’s letter-advertisement succinctly stated, “WHEREAS I the Subscriber signed an Address to the late Governor Hutchinson — I wish the devil had had said Address before I had seen it.” Prentice’s letter-advertisement contained an identical message. Among the others that ran in the Essex Gazette, Glover asserted that he signed the address “without any View of injuring the Liberties of my Country, which I ever held sacred.” Prince declared that he made “an Error in Judgment” without any “Design of injuring the Liberties of my Country, which I ever held sacred.” Those two letter-advertisements had variations in wording yet had a similar structure. For instance, Glover concluded with expressing his “hope the Publick will freely forgive this Error in their humble Servant,” while Prince stated, “I hope the Publick will freely forgive their humble Servant.”

In “Entering the Lists: The Politics of Ephemera in Eastern Massachusetts, 1774,” William Huntting Howell examines other recantations that were either similar or identical. He questions whether any of them expressed sincerely held beliefs given that they seemed to be “performing by rote.”[1] That aspect of Fowle’s letter-advertisement calls into question Glover’s invocations of “the Liberties of my Country, which I ever held sacred” and Flagg’s much more extensive reflection on his role in what had transpired. Furthermore, Howell argues, “recantations like these might have kept the Committee of Safety away from one’s house, or signaled to one’s neighbors that one no longer wished to disagree, but they cannot possibly have represented a legitimate conversion or deeply held belief.”[2] That being the case, the signatories made public apologies in hopes of getting along with others. By offering the identical letter-advertisements by Fowle and Prentice as prescriptive models for others to copy when ready to make their own “Declarations and Acknowledgments,” the Fleets also signaled that they also believed, as Howell puts it, that “the rote expression of allegiance is not the antithesis of ‘true patriotism,’ but rather its very essence. The public spectacle of apology or ‘patriotic’ conversion – especially one that follows a pattern – better serves the larger cause than a private change of heart.”[3]

**********

[1] William Huntting Howell, “Entering the Lists: The Politics of Ephemera in Eastern Massachusetts, 1774,” Early American Studies 9, no. 1 (Winter 2011): 214.

[2] Howell, “Entering the Lists,” 215.

[3] Howell, “Entering the Lists, 215-6.