What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

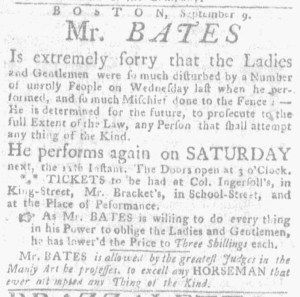

“Mr. BATES Is extremely sorry that the Ladies and Gentlemen were so much disturbed by a Number of unruly People.”

Mr. Bates’s first performance in Boston did not go as well as he hoped. Some sort of fracas interrupted his exhibition of feats of horsemanship, something significant enough to merit an advertisement in the Massachusetts Gazette and Boston Weekly News-Letter the day after that inaugural performance. Bates declared that he was “extremely sorry that the Ladies and Gentlemen were so much disturbed by a Number of unruly People on Wednesday last when he performed.” He also expressed dismay at “so much Mischief done to the Fence,” threatening “to prosecute to the full Extent of the Law, any Person that shall attempt any thing of the Kind” during subsequent performances.

Whatever disorder occurred at that performance may have worked to Bates’s advantage. Residents of Boston likely gossiped about the disruption, spreading word about Bates’s show when they did so. Some colonizers may have become more curious to attend the next performance, both to see Bates riding “One, Two, and Three HORSES,” as he promised in his previous advertisement, and to observe whether the crowd behaved or repeated the commotion from the first performance. Watching the audience had the potential to provide as much entertainment as the show, a situation perhaps not lost on Bates. After all, he collected revenue no matter what motivated Bostonians to purchase tickets.

To further encourage sales and attendance, Bates announced that he “lower’d the Price to Three Shillings each,” part of his commitment “to do every thing in his Power to oblige the Ladies and Gentlemen” of the town. Just in case some readers had not yet heard of him and his reputation, either via newspaper advertisements or word of mouth, Bates concluded his advertisement with a summary of the introduction that he inserted in other newspapers earlier in the week. He trumpeted, “Mr. BATES is allowed by the greatest Judges in the Manly Art he professes, to excel any HORSEMAN that ever attempted any Thing of the Kind.” Like other itinerant performers, Bates resorted to superlatives to market his show, promising a spectacle that exceeded anything audiences could view in Boston or anywhere else.