What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago this week?

“He has settled a Correspondence in London, whereby he acquires the first fashions of the Court.”

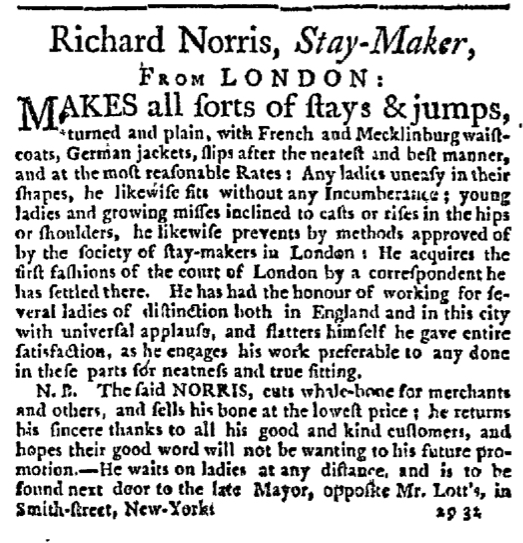

Richard Norris, a “STAY MAKER, from LONDON,” regularly placed advertisements in New York’s newspapers during the era of the American Revolution. Even as the imperial crisis heated up following the battles at Lexington and Concord in the spring of 1775, he emphasized his connections to London and knowledge of the current fashions there as he marketed the corsets he made. After all, most colonizers still looked to the largest and most cosmopolitan city in the empire for the latest trends even if they happened to have concerns with how the Coercive Acts and other abuses perpetrated by Parliament.

In an advertisement in the May 25, 1775, edition of the New-York Journal, for instance, Norris declared that he fitted his clients “by methods approved by the Society of Stay Makers in London” and noted that he “has had the honour of working for several ladies of distinction, both in England and this City, with universal applause.” By that time, he had been in New York for nearly a decade. He placed an advertisement in the New-York Mercury on March 3, 1776. The Adverts 250 Project first featured Norris with his advertisement that ran in the New-York Journal on June 23, 1768. Even though he continued to describe himself as a “STAY MAKER, from LONDON” in 1775, it had been quite some time since he practiced his trade there. Yet his clients did not need to worry about that because Norris “has settled a Correspondence in London, whereby he acquires the first fashions of the Court.” That being the case, he proclaimed with confidence that he delivered the “newest fashions from London.” In addition, he asserted “his work to be as good as any done in these parts, for neatness [and] true fitting.”

Norris also resorted to a familiar marketing strategy, encouraging women to feel anxious about their appearance, especially the shape of their bodies, to convince them to seek out his services. He addressed “Ladies who are uneasy in their shapes” and emphasized that wearing his stays “prevents the casts and risings in the hips and shoulders of young Ladies and growing Misses, to which they are often subject.” Norris considered this copy so effective that he recycled it several times over the years, honing a strategy that eventually became a staple of marketing in the modern beauty industry.