What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“West-India and New-York rum.”

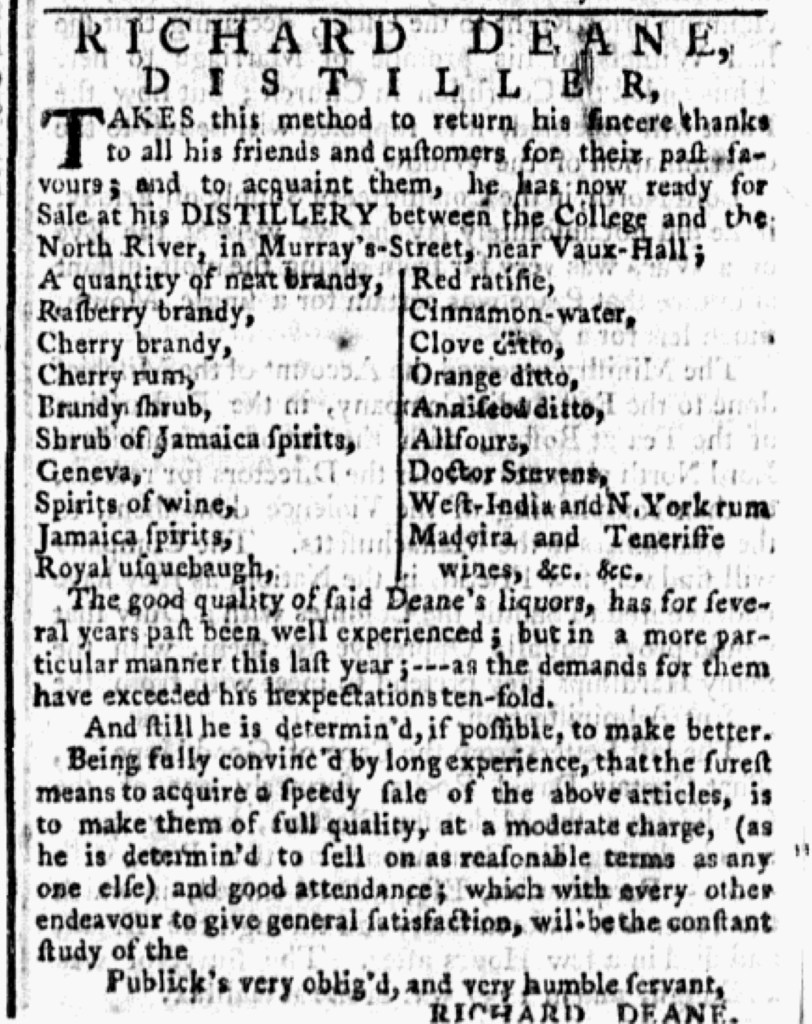

Delia Lee, a student in my Revolutionary America class, selected advertisements placed by local distillers in the April 4, 1774, edition of the New-York Gazette and Weekly Mercury to feature today. Richard Deane frequently placed advertisements in the public prints. The Adverts 250 Project previously examined one of his advertisements that he ran in the New-York Journal in 1772. Philip Kissick, “DISTILLER and VINTNER,” on the other hand, is making his first appearance among on the Adverts 250 Project.

Delia, who was enrolled in business courses at the same time she was studying Revolutionary America, was interested in the production, distribution, and consumption of alcohol in early America. When she set about her research, she consulted W.J. Rorabaugh’s overview of “Alcohol in America” in the OAH Magazine of History.[1] According to Rorabaugh, “By 1770 Americans consumed alcohol, mostly in the form of rum and cider, routinely with every meal.” Deane and Kissick stood ready to meet that demand. Both included “West-India and New-York rum” among the lists of spirits that they sold. Rorabaugh also notes that each colonizer “consumed about three and a half gallons of alcohol per year.” Deane asserted that demand for his “Rasberry brandy,” “Cherry rum,” “Shrub of Jamaica spirits,” and other products “exceeded his expectations ten-fold,” suggesting a brisk market, especially for his wares.

Over the next couple of decades, the American Revolution and its aftermath “drastically changed drinking habits. When the British blockaded the seacoast and thereby cut off molasses and rum imports, Americans looked for a substitute.” Whiskey, distilled by Scot-Irish immigrants on the western frontier, replaced rum at the end of the eighteenth century “since the British refused to supply it and the new federal government began to tax it in the 1790s.” Neither Deane nor Kissick included whiskey among the many spirits they advertised on the eve of the American Revolution. Their advertisements provide a snapshot of the alcohol industry in the colonies at that time, an industry that politics and war would soon alter in significant ways.

**********

[1] W.J. Rorabaugh, “Alcohol in America,” OAH Magazine of History 6, no. 2 (Fall 1991): 17-19.