What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

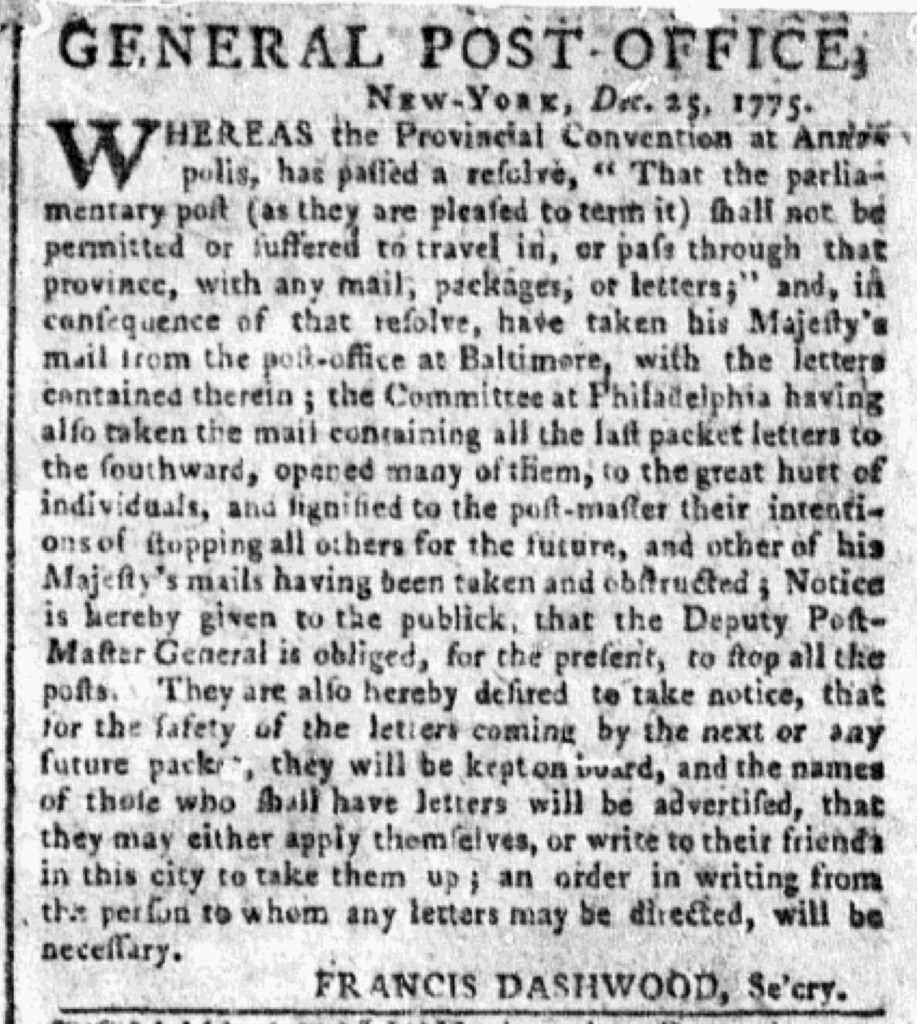

“The Deputy Post-Master General is obliged, for the present, to stop all the posts.”

In the summer and fall of 1775, advertisements for local Constitutional Post Offices, established by the Second Continental Congress as an alternative to the imperial system, appeared in newspapers printed in several colonies. Postmasters provided schedules. Post riders offered their services. As winter arrived, the Deputy Postmaster General of the “parliamentary post (as [supporters of the American cause] are pleased to term it)” published an advertisement announcing that he “is obliged, for the present, to stop all the posts.” He did not cite competition from the Constitutional Post. Instead, he blamed the actions of provincial conventions meeting in some of the colonies and abuses by rogues who tampered with private letters.

In Maryland, for instance, one of those conventions passed a resolve that “the parliamentary post … shall not be permitted or suffered to travel in, or pass through, that province, with any mail, packages, or letters.” In turn, they had confiscated “his Majesty’s mail from the post-office at Baltimore.” Similarly, a committee in Philadelphia seized “the last packet letters to the southward … and signified to the post-master their intentions of stopping all others for the future.” That was not all! That committee also “opened many of [the letters], to the great hurt of individuals,” engaging in some of the same behavior that had caused William Goddard first to envision the Constitutional Post and then advocate that the Second Continental Congress officially endorse it. The Deputy Postmaster General suggested that it was the Sons of Liberty and their supporters who had infringed on the liberties of others.

Yet this did not end the imperial postal system, though the procedures for delivering letters changed: “for the safety of the letters coming by the next or any future packet,” a ship that carried mail, “they will be kept onboard, and the names of those who shall have letters will be advertised.” Even if Hugh Gaine, the printer of the New-York Gazette and Weekly Mercury who had recently published a local edition of the Journal of the Proceedings of the Continental Congress, did not care for every British policy, he almost certainly welcomed the advertising revenue for running this notice and the prospects for publishing lists of those who had letters waiting for them aboard packet ships in the harbor. He was not a staunch patriot like John Holt, printer of the New-York Journal, and John Anderson, printer of the Constitutional Gazette, helping to explain why the advertisement concerning the “GENERAL POST-OFFICE” first appeared in his newspaper.