What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

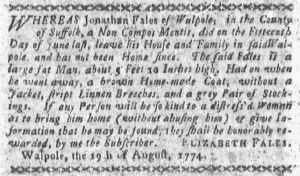

“Bring him home (without abusing him) or give Information that he may be found.”

Newspaper advertisements carried all sorts of local news that printers did not otherwise select for inclusion in their publications, keeping readers apprised of both ordinary and extraordinary occurrences. A variety of legal notices, for instance, provided news about the finances and deaths of colonizers, while other advertisements revealed marital discord when husbands decreed that they would not pay the debts of their wives. Some advertisements provided coverage of thefts and burglaries. Many described runaway apprentices and indentured servants or enslaved men and women who liberated themselves by running away from their enslavers. In most colonial newspapers, the local news section was quite short, especially compared to the amount of space devoted to news from England, Europe, and other colonies. Many historians have explained that news of local events of consequence spread via word of mouth before printers had the chance to take their weekly newspapers to press. Yet that perspective overlooks the extensive local news that appeared among advertisements.

Among their other purposes, advertisements sometimes served as missing persons notifications. Such was the case in June 1774 when Jonathan Fales of Walpole, a “Non Compos Mentis” or a man with cognitive disabilities, disappeared from “his House and Family … and has not been Home since.” Elizabeth Fales, perhaps his mother, sister, or wife, placed an advertisement in the August 22 edition of the Boston-Gazette, stating that Jonathan had not been seen for more than two months and requesting aid in finding and returning him to his family. She gave a short physical description and described the clothes he wore “when he went away.” Her concern was apparent, both in calling herself a “distress’d Woman” and pleading that anyone who found Jonathan “bring him home (without abusing him).” Elizabeth and her family cared for and protected the “large fat Man” at home, but he risked others taking advantage of him or treating him cruelly on his own. Elizabeth promised a reward to anyone who brought Jonathan home or provided “Information that he may be found.” Placing an advertisement allowed her to disseminate local news that was most important to her and her family.