What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

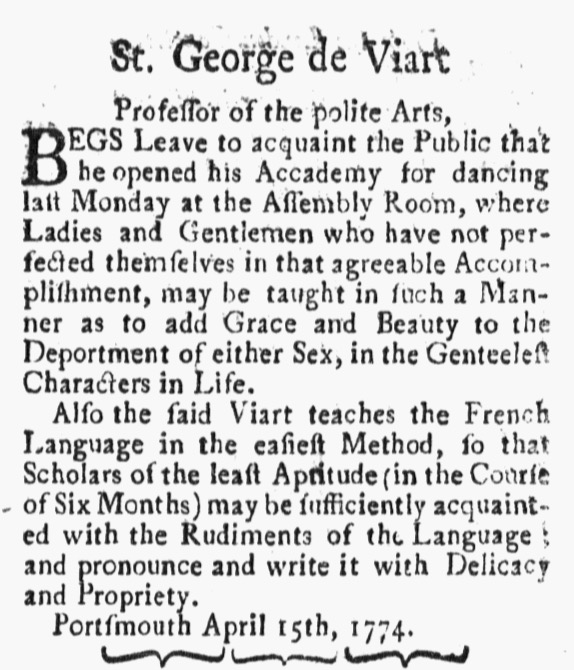

“Taught in such a Manner as to add Grace and Beauty to the Deportment of either Sex.”

Monsieur Viart once again took to the pages of the New-Hampshire Gazette in the spring of 1774, announcing that he “opened his Accademy for dancing last Monday at the Assembly Room” in Portsmouth. Viart had previously advertised in that newspaper in the summer of 1772 and as spring approached in 1773, but by the end of the summer he was running notices in the Pennsylvania Journal. Perhaps he had experienced too much competition with Edward Hackett and decided that he might have better prospects in Philadelphia, the largest and most genteel city in British North America. Whatever his motivation, Viart’s time in the Quaker City did not last long. That city had plenty of dancing masters and French tutors, a factor that may have influenced Viart’s decision to return to a place where he had cultivated a reputation among prospective students.

His presence in Portsmouth suggests a market for his services even in smaller towns, not just the largest urban ports like Boston, Charleston, New York, and Philadelphia. Viart described himself as a “Professor of the polite Arts,” signaling that his instruction aided students in maintaining or improving their status as they strove to display their gentility to others. He provided dancing lessons to “Ladies and Gentlemen who have not perfected themselves in that agreeable Accomplishment,” promising that he taught “in such a Manner as to add Grace and Beauty to the Deportment of either Sex, in the Genteelest Characters in Life.” In addition to dancing, Viart “teaches the French Language in the easiest Method.” He reassured even the most anxious prospective students, those “Scholars of the least Aptitude,” that in just six months they “may be sufficiently acquainted with the Rudiments of the Language” that they would “pronounce and write it with Delicacy and Propriety.” Viart’s advertisements in the New-Hampshire Gazette demonstrate that just as the consumer revolution reached far beyond major port cities and into smaller towns and even the countryside, so too did concerns with refinement of character and comportment. As colonizers acquired more goods and associated meaning with them, they also recognized that dancing well and speaking French testified to their gentility and validated their choices to wear fine clothing and purchase fashionable housewares. As a “Professor of the polite Arts,” Viart marketed skills that helped his students complete the picture of their “Genteelest Characters.”