GUEST CURATOR: Nicholas Arruda

What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago this week?

“MADEIRA Wine.”

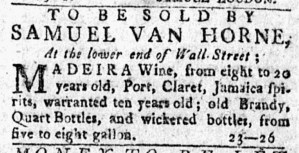

Samuel Van Horne advertised “MADEIRA Wine, from eight to 20 years old, Port, Claret, Jamaica spirits, [and] old Brandy” in the New-York Journal on February 1, 1776. Mentioning that the Madeira was aged between eight and twenty years might have meant that Van Horne was focusing on elite consumers who used imported wines to show their refinement since Madeira wine was not an everyday beverage. As David Hancock explains, in the eighteenth century, Madeira was “an expensive, exotic, status-laden, and highly processed wine produced on the Portuguese island of Madeira, 500 miles west of Morocco.”[1] Its status came from its position in Atlantic trade networks. Hancock argues that the status of the wine was created through “an Atlantic network of producers, distributors, and consumers in intense conversation with one another,” which transformed Madeira into a commodity that was recognized across the British Empire.[2] Van Horne’s advertisement thus shows that selling aged Madeira was not just about selling alcohol but even more importantly participating in elite identity.

**********

ADDITIONAL COMMENTARY: Carl Robert Keyes

Regular readers of the New-York Journal saw Samuel Van Horne’s advertisement for Madeira and other wines and spirits three times before they encountered it in the February 1, 1776, edition. As the colophon at the bottom of the final page explained, “Advertisements of no more Length than Breadth are inserted for Five Shilling[s for] four Weeks, and One Shilling for each Week after, and larger Advertisements in the same Proportion.” Many newspapers printed in the colonies solicited advertisements, but they did not always indicate the fees. John Holt, the printer of the New-York Journal, hoped to entice advertisers by letting them know how much they would pay to insert notices in his newspaper. The initial charge covered the space that an advertisement occupied in four consecutive issues at one shilling per week and an additional shilling for setting the type, keeping the books, and other work undertaken in the printing office.

That makes it easy to determine that Van Horne invested five shilling in running his advertisement. Its length certainly was no more than its breadth, so the printer did not increase the fee in proportion as he did for longer advertisements. The notation in the lower right of the advertisement, “23-26,” makes clear that Van Horne intended for the advertisement to run only for the four weeks covered by the initial expense. “23” referred to the issue number for the first issue that carried the advertisement, “NUMBER 1723” on January 11, while “26” indicated the final issue to carry the advertisement, “NUMBER 1726” on February 1. At a glance, the compositor knew whether to include Van Horne’s advertisement in a new issue or remove it. The notation, intended for employees in the printing office rather than readers of the newspaper, made it unnecessary to consult a ledger, instructions from the advertiser, or other documents. Van Horne apparently decided that he did not wish to extend the run of this advertisement. The compositor did indeed remove it rather than publish it once again in the February 8 edition.

**********

[1] David Hancock, “Commerce and Conversation in the Eighteenth-Century Atlantic: The Invention of Madeira Wine,” Journal of Interdisciplinary History 29, no. 2 (Autumn 1998): 197.

[2] Hancock, “Commerce and Conversation,” 197.