What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago this week?

“Advertisements, blanks, and many other kinds of printing work, she ardently hopes, may be discharged at the general courts.”

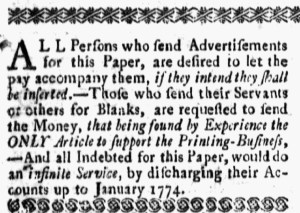

Clementina Rind printed the Virginia Gazette and operated the printing office following the death of her husband in August 1773. That included keeping the books and calling on customers to settle accounts. She issued such a notice in the April 14, 1774, edition of her newspaper, at the same time outlining improvements to the publication that payments would help support. She asserted that she had “lately considerably enlarged her paper,” providing more content to subscribers and other readers. In addition, she ordered and “expect[ed] shortly an elegant set of types from London, … together with all other materials relative to the printing business.” Rind expressed pride in “the dignity of her gazette” while simultaneously noting that those who owed money had a role to play in her goal of “keeping it at a fixed standard.”

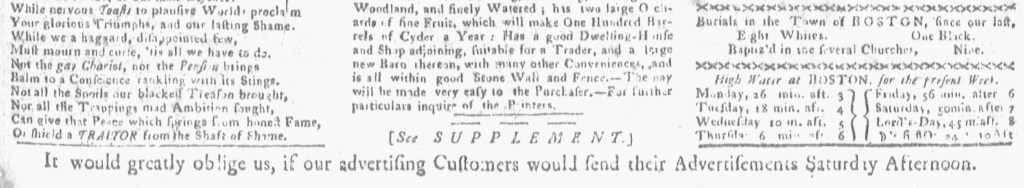

To that end, she called on subscribers to submit annual payments. In the eighteenth century, many newspaper subscribers notoriously went for years without settling accounts with printers. Advertising revenue offset those delinquent payments, yet not all printers demanded that advertisers pay for their notices in advance, contrary to common assumptions about how they ran their businesses. Rind’s notice suggests that she may have published advertisements on credit but does not definitively demonstrate that was the case. She requested that customers pay what they owed for “advertisements, blanks, and many other kinds of printing work … at the general courts.” She may have meant newspaper notices, but “advertisements” could have also referred to handbills, broadsides, and other job printing for the purposes of marketing goods and services or disseminating information to the public. The masthead listed prices for subscriptions (“12 s. 6 d. a Year”) and advertisements “of a moderate length” (“3 s. the first Week, and 2 s. each Time after”), while also promoting “PRINTING WORK, of every Kind,” which would have included blanks (or forms for legal and commercial transactions), handbills, and broadsides, but that does not clarify what Rind meant by “advertisements” in her notice. That other printers sometimes allowed credit for newspaper advertisements leaves open the possibility that Rind may have done so as well. If that was the case, it made it even more imperative that advertisers discharge their debts to “enable her the better to carry on her paper with that spirit which is so necessary to such an undertaking.”