Who was the subject of an advertisement in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“A Negro answering the above Discription has let himself to Mr. Jesse Leavensworth of New-Haven.”

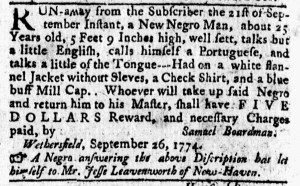

In the fall of 1774, Samuel Boardman of Wethersfield took to the pages of the Connecticut Courant and Hartford Weekly Intelligencer to offer a reward for the capture and return of a “New Negro Man” who liberated himself by running away. Boardman did not give a name for this man, but instead stated that he “talks but a little English, calls himself a Portuguese, and talks a little of the Tongue.” He offered a reward to “Whoever will take up said Negro and return him to his Master.” Dated September 26, the advertisement first appeared in the October 3 edition of the Connecticut Courant. It included a notation indicating that a “Negro answering the above Discription has let himself to Mr. Jesse Leavensworth of New-Haven.” Boardman most likely did not include that information in the copy he submitted to the printing office.

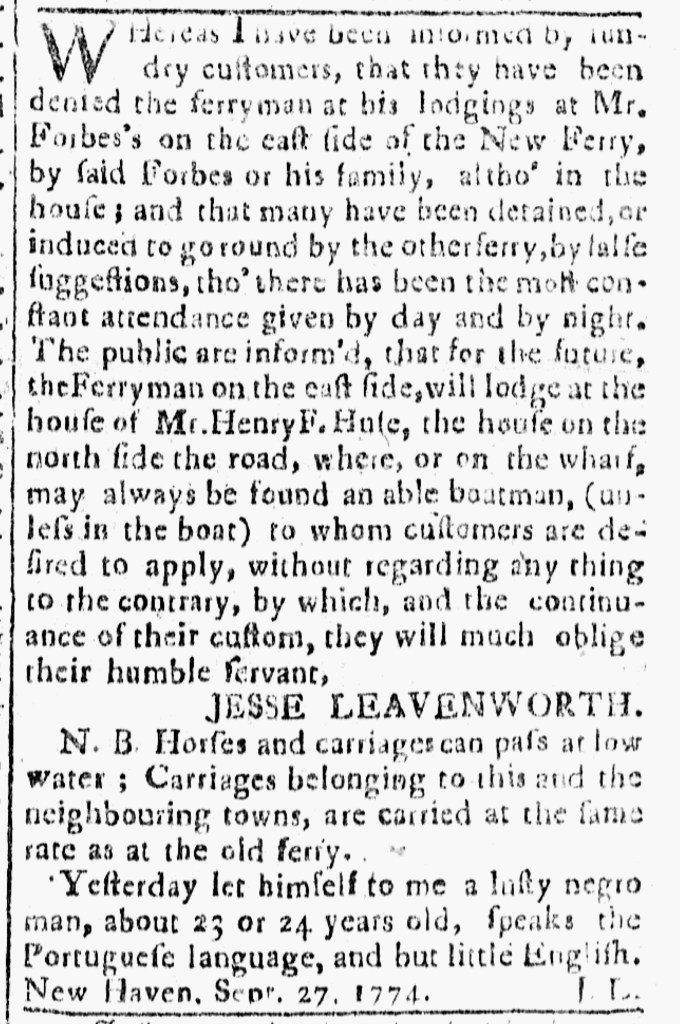

Instead, Ebenezer Watson, the printer, likely supplied it upon reading an advertisement that Leavenworth placed in the September 30 edition of the Connecticut Journal and New-Haven Post-Boy. After all, printers regularly exchanged newspapers in hopes of acquiring content for their own publications. Leavenworth devoted most of that notice to giving instructions for hiring his ferry, but added a note that recently a “lusty negro man, about 23 or 24 years old, speaks the Portuguese language, but little English” had “let himself to me.” Leavenworth hired the young man, but was suspicious that he was a fugitive seeking freedom and his enslaver was looking for him. Just in case, he supplemented his advertisement for the ferry with the description of the Black man who spoke Portuguese. Given the timing of the advertisements in the two newspapers, Boardman would not have seen Leavenworth’s notice when he drafted his own advertisement. If he had that information, he could have dispensed with advertising at all.

What role did Watson play in keeping Boardman informed about this development? He might have dispatched a message to the advertiser in Wethersfield, though he could have considered the note at the end of the advertisement sufficient to update Boardman, figuring that his customer would check the pages of the Connecticut Courant to confirm that his notice appeared. Watson could have also sent a message to Thomas Green and Samuel Green, the printers of the Connecticut Journal, along with his exchange copy of the Connecticut Courant, expecting they might pass along the information to Leavenworth. In addition, Leavenworth might have eventually encountered Boardman’s advertisement, depending on his reading habits, or otherwise heard about it. That alternative seems most likely. No matter what other action Watson took, inserting the note that connected the unnamed Black man in Boardman’s advertisement in the Connecticut Courant to the unnamed Black man in Leavenworth’s advertisement in the Connecticut Journal alerted readers that they could collect the reward if they decided to pursue the matter. The power of the press, including a printer whose assistance extended beyond merely setting type and disseminating the advertisement, worked to the advantage of Boardman, the enslaver, against the interests of the unnamed Black man who spoke Portuguese.