What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“PHILADELPHIA CONSTITUTIONAL POST-OFFICE.”

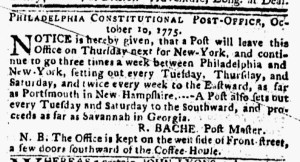

At the same time that Mary Katharine Goddard, postmaster and printer of the Maryland Journal, advertised the Baltimore branch of the Constitutional Post Office in the fall of 1775, Richard Bache ran a notice for the “PHILADELPHIA CONSTITUTONAL POST-OFFICE” in the October 13 edition of Story and Humphreys’s Pennsylvania Mercury. Although Bache was not the printer of that newspaper, his advertisement received a privileged place similar to the one that Goddard’s notice enjoyed in her newspaper. It appeared first among the advertisements that readers encountered when they perused the newspaper from start to finish, immediately below the “SHIP NEWS” and list of “ARRIVALS” in Philadelphia. A double line did separate news from advertising, yet this item delivered news relevant to the imperial crisis that had become a war with the battles at Lexington and Concord the previous spring. Over the summer, the Second Continental Congress established the Constitutional Post Office as an alternative to the imperial post office. Enoch Story and Daniel Humphreys, the printers of the newspaper that carried Bache’s advertisement, apparently considered it in their best interest to increase the likelihood readers would take note of the information about the Constitutional Post Office by placing the notice right after the news.

Compared to Goddard’s advertisement, Bache’s notice gave readers a much more expansive glimpse of the scope of the enterprise. Rather than simply stating which days the post arrived and departed, Bache reported that the Constitutional Post carried letters and newspapers “as far as Portsmouth in New-Hampshire” to the north and “as far as Savannah in Georgia” to the south. The system linked the thirteen colonies. On Tuesdays, Thursdays, and Saturdays, a rider set out for New York from Philadelphia. On Tuesdays and Saturdays, another rider headed “to the Southward” to Baltimore, arriving there, according to Goddard’s advertisement, on Mondays and Thursdays. This new system did more than move mail. “Establishing a new post office,” Joseph M. Adelman argues, “placed the levers of information circulation in the hands of Americans. … Forming a ‘continental’ post office that could properly embody an intercolonial union and its resistance to imperial tyranny was crucial to Patriot mobilization at the height of the imperial crisis.” Furthermore, “Patriot printers and their radical friends” played an integral role in establishing the new postal system.[1] No wonder that Story and Humphreys placed Bache’s advertisement about the “PHILADELPHIA CONTSITUTIONAL POST-OFFICE” right after the “SHIP NEWS.”

**********

[1] Joseph M. Adelman, “‘A Constitutional Conveyance of Intelligence, Public and Private’: The Post Office, the Business of Printing, and the American Revolution,” Enterprise and Society 11, no. 4 (December 2010): 747-748.