What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago this week?

“Her husband has absconded, to avoid the payment of his debts.”

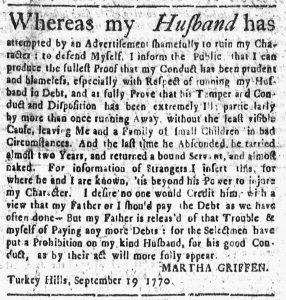

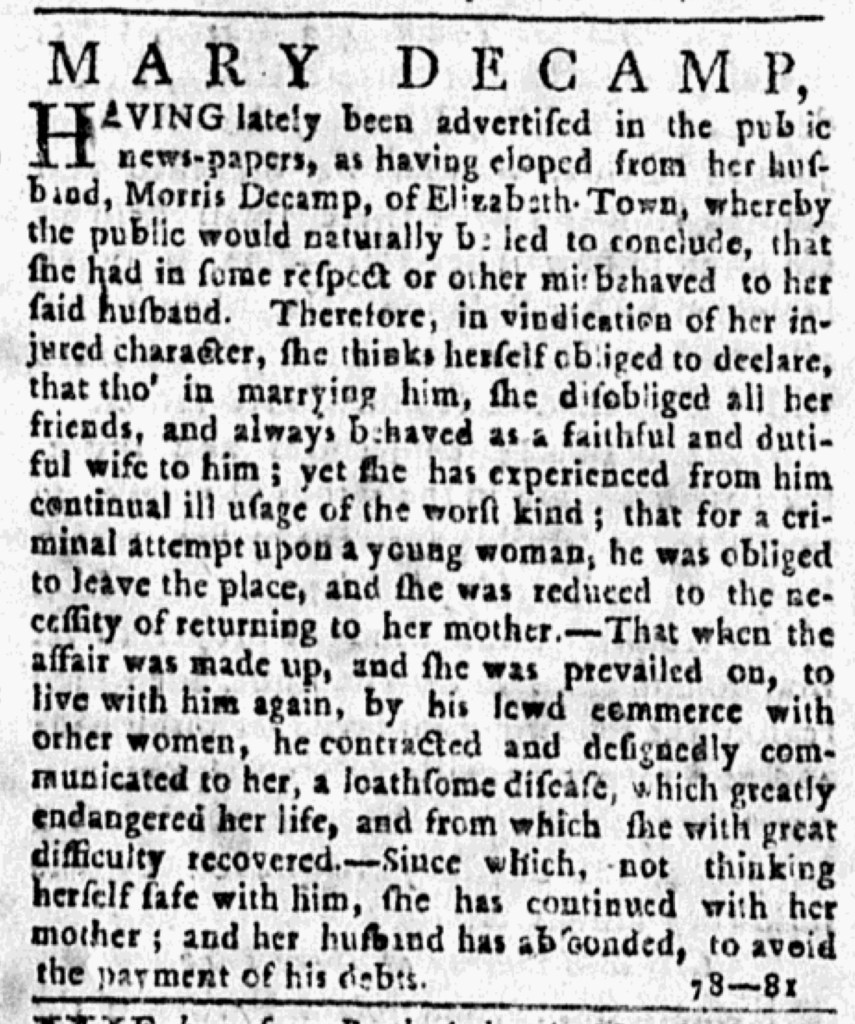

It began as a standard “runaway wife” advertisement in the January 19, 1775, edition of the New-York Journal. “WHEREAS my Wife Mary has lately eloped from me, and my perhaps endeavour to run me into Debt,” Morris Decamp proclaimed, “these are therefore to warn all Persons not to Trust or entertain her on my Account, as I will pay no Debts she may contract.” That advertisement ran for four weeks, but not without going unnoticed or unanswered by Mary.

Most women who appeared in the public prints as the subject of such advertisements did not have the means or opportunity to respond. Mary, however, did, perhaps with assistance from some of her relations. Her own advertisement began its run in the March 2 edition of the New-York Journal, placing it before the eyes of the same readers who saw her husband’s missive. She acknowledged that “the public would naturally be led to conclude, that she had in some respect or other misbehaved to her said husband” based on what they knew from his advertisement. On the contrary, she asserted, she “always behaved as a faithful and dutiful wife to him.” The misbehavior had been solely on his part. Mary “experienced from him continual ill usage of the worst kind,” yet his villainy extended beyond their household. The aggrieved wife alleged that Morris committed “a criminal attempt upon a young woman” that resulted in him having to leave town. Abandoned by her husband, Mary “was reduced to the necessity of returning to her mother.” Morris somehow managed to resolve that situation; Mary did not provide details but reported that “when the affair was made up, … she was prevailed on, to live with him again,” much to her regret. Her husband remained unreformed: “by his lewd commerce with other women, he contracted and designedly communicated to [Mary], a loathsome disease, which greatly endangered her life, and from which she with great difficulty recovered.”

The real story, Mary insisted, reflected poorly on her husband, not on her. She took to the pages of the New-York Journal“in vindication of her injured character.” Rather than “eloping” from Morris, she had returned to her mother because she did not consider herself safe with him. It was actually Morris who “has absconded, to avoid the payment of his debts.” Even as he tried to cut her off from his credit, her notice likely prompted others to think twice about doing business with him. Wives rarely placed rebuttals to the advertisements published by their husbands. In the rare instances that they did, women like Mary Decamp attempted to harness the power of the press to defend their reputations by setting the record straight.