What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

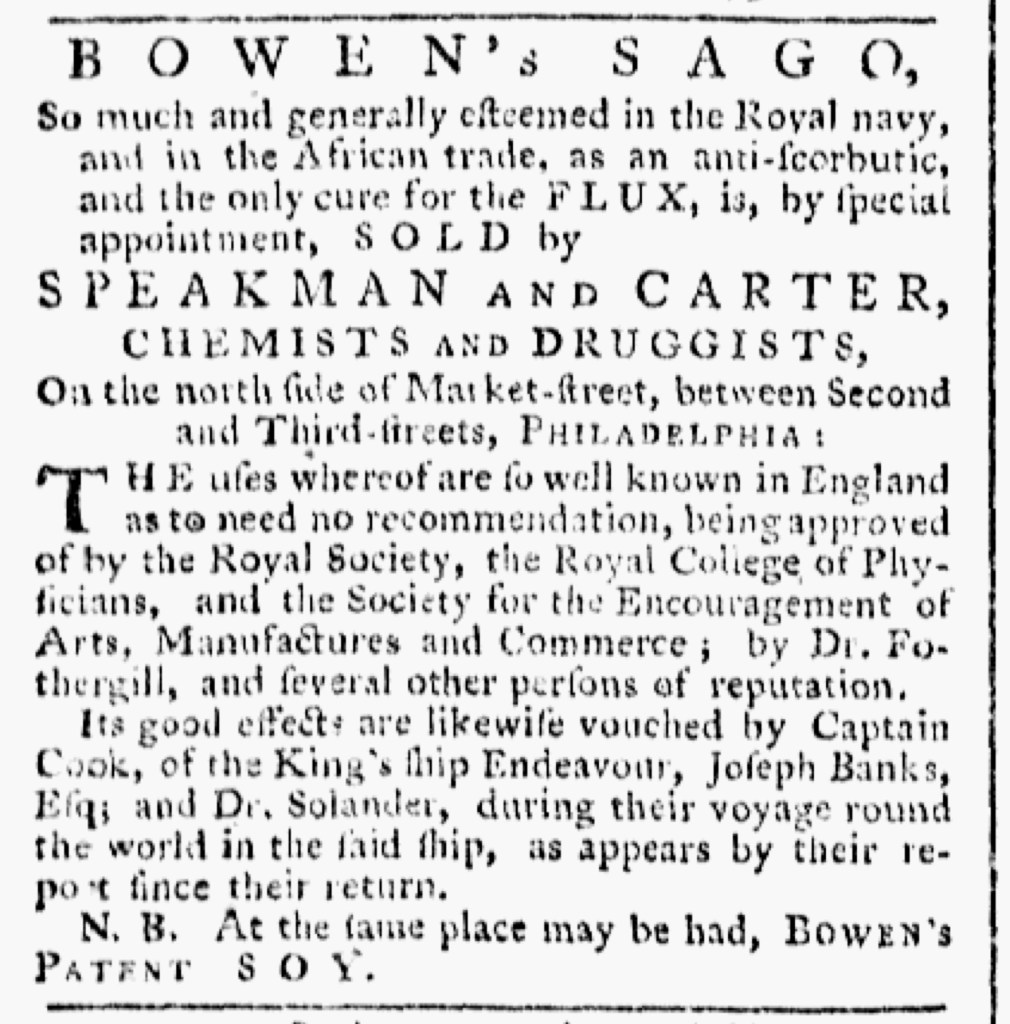

“BOWEN’s SAGO … the only cure for the FLUX.”

Townsend Speakman and Christopher Carter, “CHEMISTS AND DRUGGISTS” in Philadelphia, took to the pages of Dunlap’s Pennsylvania Packet to advertise “BOWEN’s SAGO,” a medicine for preventing and curing scurvy. The apothecaries did not, however, appear to generate their own copy. Instead, they seemed to borrow heavily from advertisements that Zepheniah Kingsley placed in the South-Carolina Gazette and Country Journal and other newspapers published in Charleston several months earlier.

The headline differed only slightly, “BOWEN’s patent SAGO” in the original shortened to “BOWEN’s SAGO” in Speakman and Carter’s advertisement. The introductory remarks remained the same, describing the product as “So much and generally esteemed in the Royal navy, and in the African trade, as an anti-scorbutic, and the only cure for the FLUX.” In the original, the retailer then announced, “SOLD By Z. KINGSLEY,” and directed customers to his store in Beadon’s Alley. The apothecaries in Philadelphia altered that portion slightly, declaring that the medicine “is, by special appointment, SOLD by SPEAKMAN AND CARTER, CHEMISTS AND DRUGGISTS,” and then gave directions to their shop. The main body of both advertisements included an overview of endorsements by “the Royal Society, the Royal College of Physicians, and the Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce.” Speakman and Carter added additional endorsements: “by Dr. Fothergill, and several other persons of reputation.” Another paragraph described how Captain James Cook and botanists who sailed with him during the Endeavour’s “voyage round the world” also “vouched” for the “good effects” of Bowen’s Sago in the report they published upon their return. It appeared almost word-for-word, substituting “Joseph Banks, Esq” for “Mr. BANKES.” A brief note appeared at the end, “SOLD at same Place, BOWEN’s patent SOY” in the original and “At the same place may be had, BOWEN’S PATENT SOY.”

Speakman and Carter created their advertisement at a time that most people thought little of reprinting what others had written or published, at least in certain contexts. Colonial printers liberally reprinted content from one newspaper to another, often attributing their sources but sometimes not doing so. Printers and booksellers who advertised books frequently copied the extensive subtitles or contents that appeared on the title page, treating those as advertising copy. Apothecaries, shopkeepers, and others who sold patent medicines sometimes published newspaper advertisements that drew heavily from the directions or promotional materials provided by the producers. In this instance, Speakman and Carter may have used Kingsley’s advertisement as a model, revising it slightly for their purposes, or both the apothecaries in Philadelphia and the merchant in Charleston may have adapted handbills, newspaper advertisements, or other marketing materials sent to them by their suppliers. Whatever the explanation, consumers in two major ports encountered nearly identical marketing for a product sold by local vendors.