What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago this week?

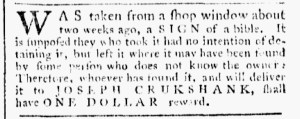

“WAS taken from a shop window … a SIGN of a bible.”

Joseph Crukshank ran a printing office and sold books at the “SIGN of a bible” in Philadelphia … some of the time. According to an advertisement that he placed in the January 17, 1774, edition of Dunlap’s Pennsylvania Packet, his sign went missing sometime around the beginning of the year. When he started in the trade, Crukshank did an apprenticeship with Andrew Steuart “at the Bible-in-Heart.”[1] Perhaps he chose a similar device to mark his location as a means of encouraging an association in the minds of prospective customers familiar with his former master’s work.

“WAS taken from a shop window about two weeks ago,” Crukshank stated, “a SIGN of a bible.” In that notice, the printer and bookseller provided information that testified to the visual culture of advertising that colonizers encountered when they traversed the streets of Philadelphia. Although some eighteenth-century trade cards depict shop signs hanging from poles, presumably outside and perhaps perpendicular to the building so pedestrians could see them from a distance, Crukshank apparently positioned his sign in a window, facing into the street. That gave it less visibility, but likely required less maintenance by protecting it from the weather. Unfortunately, Crukshank did not indicate the size of the sign, though it must have been small enough for whoever took it to carry away without attracting notice.

The printer and bookseller did not believe that the culprit kept the sign but instead played a trick by abandoning it somewhere. “It is supposed they who took it had no intention of detaining it,” he declared, “but left it where it may have been found by some person who does not know the owner.” With that statement, Crukshank confessed the limits of deploying an image to represent his business. Colonizers who lived in his neighborhood almost certainly recognized the “SIGN of a bible” that identified his shop, as did many others who had resided in the city for some time. Yet he did not consider the image universally known among the denizens of the busy port. His advertisement may have aided to establish a connection between Crukshank’s shop and his sign in the minds of those readers, a helpful bit of branding if he managed to recover the sign or replaced it.

**********

[1] Isaiah Thomas, The History of Printing in America: With a Bibliography of Printers and an Account of Newspapers (1810; New York: Weathervane Books, 1970), 386.