What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“George Bartram intends to decline the retail trade, so soon as the trade is open between Britain and America.”

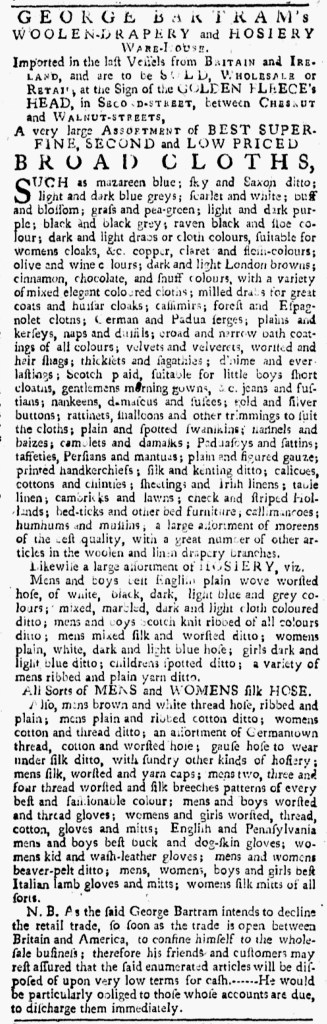

As September 1775 came to a close, George Bartram advertised a “very large ASSORTMENT of BEST SUPERFINE, SECOND and LOW PRICED BROADCLOTHS” and “a large assort of HOSIERY” available at his “WOOLEN-DRAPERY and HOSIERY WARE-HOUSE … at the Sign of the GOLDEN FLEECE’s HEAD” in Philadelphia. He listed dozens of different kinds of textiles and hose for men, women, and children as well as an array of gloves and mittens. Bartram stated that he imported that merchandise “in the last Vessels from BRITAIN and IRELAND,” but he may have meant the last ships to arrive before the Continental Association went into effect nearly ten months earlier. After all, he acknowledged in a nota bene that the colonies were not trading with Britain at the time he placed his advertisement.

That nota bene also included a clarification about Bartram’s plans for his business. In March, he had advertised that he was “resolved to decline his Retail Trade” and would “sell his Stock of Goods on Hand at the very lowest Rates.” A headline proclaimed, “Now SELLING OFF.” That gave the impression that Bartram was holding a going out of business, yet his subsequent advertisement suggests that was not his intention at all. Instead, he planned to shift his emphasis. “[S]o soon as the trade is open between Britain and America,” he would “decline the retail trade … to confine himself to the wholesale business.” His “WOOLEN-DRAPERY and HOSIERY WARE-HOUSE” would not close after all, but that did not mean that customers could not find bargains when they visited the familiar Sign of the Golden Fleece’s Head. For the moment, Bartram continued to serve retail customers, assuring them that “the said enumerated articles will be disposed of upon very low terms.”

Bartram did not know when trade with Britain would resume. He placed his previous advertisement before hostilities broke out at Lexington and Concord. He attempted to earn his livelihood as he navigated current events, not knowing when the conflict would end, hoping that good deals would convince customers to continue shopping at his “WOOLEN-DRAPERY and HOSIERY WARE-HOUSE” even as they kept their eyes on news arriving from Boston.