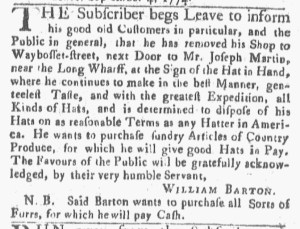

What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“He has removed his Shop to … the Sign of the Hat in Hand.”

When William Barton moved to a new location as the summer came to a close in 1774, he placed an advertisement in the Providence Gazette to inform “his good old Customers in particular, and the Public in general” where to find him. Having established a clientele, the hatter did not wish to miss out on subsequent business if customers went to his former shop and did not discover him there. All prospective customers, whether or not they previously acquired hats from Barton, could recognize his new location by the “Sign of the Hat in Hand.” The hatter did not indicate whether that marketing device had marked his previous location or if it was an innovation on the occasion of setting up shop on Weybosset Street. Either way, it became part of the landscape of advertising that colonizers encountered as they traversed the streets “near the Long Wharff” in Providence.

To entice consumers to visit his shop, Barton made a variety of appeals. He promised quality, stating that he made hats “in the best Manner.” He emphasized fashion, declaring that his hats reflected “genteelest Taste.” He touted his own skill and industriousness, asserting that “the greatest Expedition” went into producing his hats. He offered choices to consumers, proclaiming that his inventory included “all Kinds of Hats.” For his boldest appeal, he trumpeted that he was “determined to dispose of his Hats on as reasonable Terms as any Hatter in America.” Barton did not merely compare his prices to his local competitors. He confidently declared that consumers would not find any better deal anywhere, even if they sent away to Boston or New York or any other city or town in the colonies. He challenged readers to visit his shop, learn his prices, and judge for themselves. If his claim could get potential customers through the doors, that increased his chances of making sales. Though his advertisement was not particularly lengthy, Barton incorporated many of the most common marketing appeals advanced by artisans in eighteenth-century America, anticipating that they collectively became more even more convincing.