Who was the subject of an advertisement in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“SOLOMON, a negro, … will make for Boston to the soldiers.”

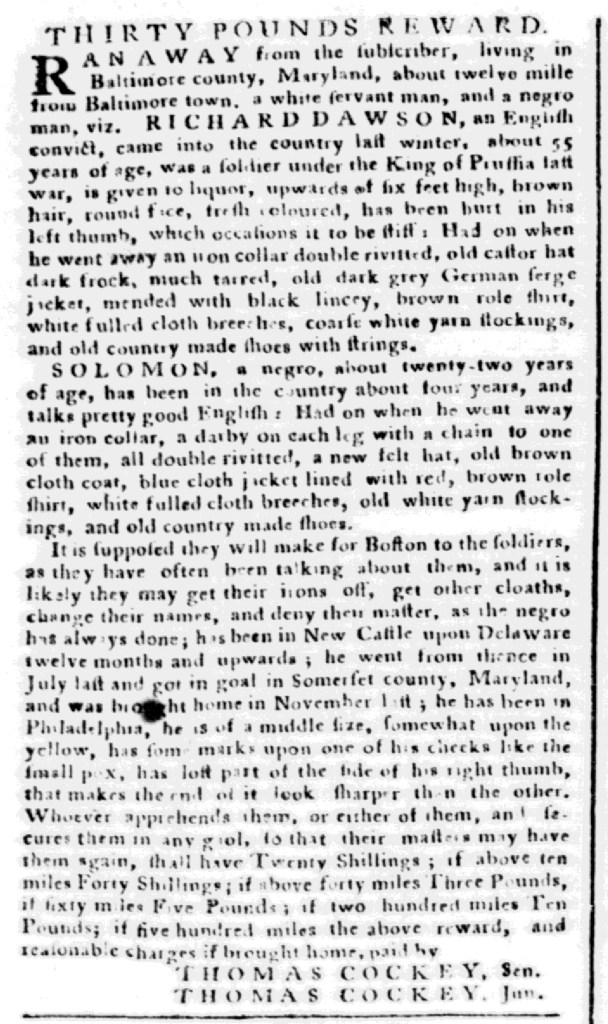

They made their escape together. Solomon, an enslaved man, and Richard Dawson, a “white servant man” and “an English convict,” ran away from Thomas Cockey, Sr., and Thomas Cockey, Jr., in Baltimore County in the spring of 1775. Their advertisement describing Solomon and Dawson first appeared in the May 16, 1775, edition of Dunlap’s Maryland Gazette. The two men apparently eluded capture because the notice ran regularly for the next several months, including in the July 4 edition.

When they departed, both Solomon and Dawson had an “iron collar double rivetted.” Solomon had also been outfitted with “a darby” or fetters “on each leg with a chain to one of them,” probably because the Cockeys correctly considered him likely to attempt to liberate himself. He did, after all, have a history of making a break for freedom. According to the Cockeys, Solomon previously made it to New Castle in Delaware, remaining there for “twelve months and upwards,” but then in July 1774 went to Somerset County, Maryland. There he was captured, jailed, and “brought home in November.” Within months, he became a fugitive seeking freedom once again. The Cockeys believed that Solomon “has been in Philadelphia.”

Solomon was a young man, “about twenty-two years of age,” who had been in the colonies “about four years.” Dawson, in contrast, was older, “about 55 years of age.” He had served as a soldier “under the King of Prussia [during the] last war.” The Cockeys did not indicate which crimes Dawson committed to merit punishment as a convict servant transported to America. They did speculate that Solomon and Dawson “will make for Boston to the soldiers, as they have often been talking about them,” though they did not reveal the particulars of what the enslaved man and the former soldier had to say about the British troops or when their conversations first occurred. Had they taken place after learning of the battles at Lexington and Concord? Did Dawson think that British soldiers might feel some sympathy for a former comrade? Did Solomon believe that regulars would shelter him from the colonizers who put him in bondage? Even if they did not hope for aid, Solomon and Dawson might have considered the upheaval in New England the best opportunity to avoid detection and capture. The Cockeys anticipated that both men would “get their irons off, get other cloaths [to disguise themselves], change their names, and deny their master.” Since Solomon “talks pretty good English” and evaded capture for so long during his previous attempt to liberate himself, he had likely learned to tell plausible stories.

Some advertisements about enslaved men and women who liberated themselves by running away from their enslavers during the era of the American Revolution suggested that they received assistance from enslaved relatives and friends. On occasion, other advertisements recorded enslaved people and unfree colonizers (indentured servants, convict servants, apprentices) working together. The role that the battles at Lexington and Concord and the siege of Boston played in Solomon’s decision to make common cause with Dawson cannot be determined from the narrative the Cockeys presented in their advertisement. What is clear, however, is that Solomon repeatedly made his own declarations of independence.

For other stories of enslaved people liberating themselves originally published on July 4 during the era of the American Revolution, see:

- An account of Caesar, a blacksmith (Providence Gazette, July 4, 1767)

- An account of Harry, his wife Peg, a free woman, and their two children (Pennsylvania Chronicle, July 4, 1768)

- An account of Guy and Limehouse, two youths (South-Carolina and American General Gazette, July 4, 1769)

- An account of Jack, a Black man, and Tony, an Indian man, who took a boat when they made their escape (South-Carolina and American General Gazette, July 4, 1770)

- An account of Violet, a woman who eluded capture by her former enslaver for at least nine years (Pennsylvania Journal, July 4, 1771)

- An account of Caesar, who liberated himself at the same time word spread about colonizers burning the Gaspee (Providence Gazette, July 4, 1772)

- A census of enslaved people who liberated themselves advertised in American newspapers in the week leading up to July 4, 1773

- George, an enslaved men “in Flushing on Long-Island,” who “RAN AWAY” as the Coercive Acts went into effect (New-York Gazette and Weekly Mercury, July 4, 1774)