GUEST CURATOR: Daniel McDermott

What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today”

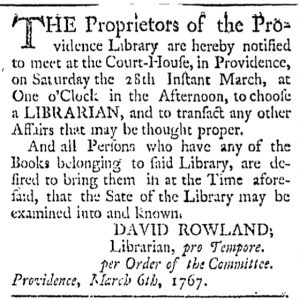

“THE Proprietors of the Providence Library are hereby notified to meet at the Court-House.”

David Rowland, “Librarian, pro Tempore,” placed this advertisement to notify “Proprietors” of the Providence Library Company (founded 1753) that a meeting was planned to elect a new Librarian on March 28. The advertisement also notified anyone who had books belonging to the library to return them.

The greatest change in libraries over time has been to access by general readers. Today, most town libraries are open to the public but require a library card to access their collection. These are the libraries used by most person. In eighteenth-century America, access to libraries was more restricted because most were based on a monthly or yearly paid membership.

According to William Burns, the two most popular types of libraries in the eighteenth century were circulating libraries and subscription libraries. Circulating libraries had lower subscription fees, paid weekly to borrow books. Subscription libraries normally had higher membership rates and were associated with reading societies.

The Junto, Benjamin Franklin’s discussion group in Philadelphia, created one of the most famous subscription libraries. It still exists today as the Library Company of Philadelphia. By the middle of the nineteenth century, the library was one of the five largest in the United States. The Library Company of Philadelphia is a good example of how libraries are valued in our society: some last multiple centuries. Over time, other libraries that give open access to the public have joined them. Although Americans did not expect to find libraries open to all in the eighteenth century, many valued libraries and the access to knowledge and entertainment they provided.

**********

ADDITIONAL COMMENTARY: Carl Robert Keyes

Printers and booksellers frequently advertised their wares in eighteenth-century newspapers, sometimes listing dozens of titles, sometimes promoting a particular book, and sometimes seeking subscribers as a means of gauging interest in books they intended to publish (provided the public responded with sufficient demand in advance). A reading revolution took place in the eighteenth century as consumers purchased greater numbers of books and their reading habits shifted from intensive reading of bibles, devotional texts, and almanacs to extensive reading from an array of genres.

The reading revolution also included the founding of private lending libraries by civic organizations, including the Library Company of Philadelphia (1731), the Charleston Library Society (1748), and the Providence Library Company (1753). Daniel has already provided a brief sketch of two models for operating libraries – subscription libraries and circulating libraries – that gave colonists greater access to books than most would have been able to purchase on their own.

As Daniel notes, subscription libraries and circulating libraries charged different rates to access their collections. In exchange for paying the fees, readers received different benefits. Members of subscription libraries paid annual fees for unlimited borrowing privileges, giving them broad access to the library company’s collections. Nonsubscribers could also borrow books, paying variable fees based on the size of the book (the dimensions of the pages – folio, octavo, duodecimo – not the length of the text) and the length of time they kept the book. On the other hand, circulating libraries did not usually have annual subscription fees. Instead, they charged by the week, which allowed patrons to keep expenses down by choosing how often to check out books. Circulating libraries also limited access to one book at a time.

Circulating libraries facilitated the reading revolution. A significant aspect of the shift from intensive to extensive reading involved the rise of the novel and reading for pleasure, especially by women. Subscription libraries tended not to obtain novels, but, as William Burns notes, novels “were the lifeblood of the circulating library.” Furthermore, “women comprised about half the membership of the circulating libraries,” but subscription libraries did not admit female readers (though that did not prevent men from checking out books for female relatives and friends).

Despite differences in membership, collections, and operating structure, both subscription libraries and circulating libraries emerged exclusively in cities in the eighteenth century, pointing to another important distinction between libraries then and now. Daniel notes that public libraries operated by local municipalities have greatly expanded access to information and services. Organizations like the Providence Library Company played an important role in that process as they allowed early Americans greater access to books than they previously experienced.