What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago this week?

“Under the inspection of Mrs. BROADFIELD, whose knowledge and experience in that branch of business is well known.”

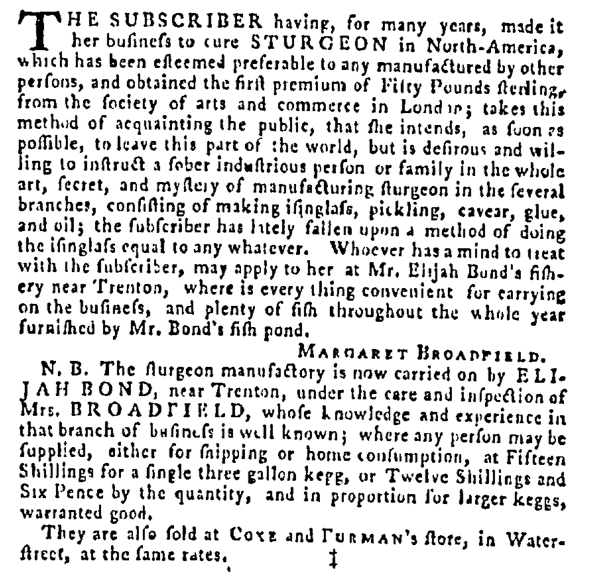

Margaret Broadfield was not exceptional for having placed an advertisement in the Pennsylvania Gazette in the late summer of 1768, though female entrepreneurs were certainly disproportionately underrepresented among advertisers in newspapers published throughout the colonies. Especially in bustling port cities, women pursued a variety of occupations but relatively few promoted their businesses in the public prints. Still, female shopkeepers, milliners, seamstresses, and others placed advertisements frequently enough that readers were accustomed to seeing women appearing alongside men among the paid notices in colonial newspapers, just as they were accustomed to encountering women working alongside men when they traversed the streets of cities and towns.

What did make Broadfield’s advertisement exceptional was the authority she asserted over a male colleague. When women and men appeared together in eighteenth-century advertisements, the copy often suggested that women played subordinate roles to their male counterparts. Such advertisements implied that women in business labored under appropriate supervision by husbands, sons, or other male relations. That was not the case with Broadfield. She made it clear that she exercised authority over a male associate, Elijah Bond, at least when it came to preparing sturgeon for the market.

For many years Broadfield had “made it her business to cure STURGEON in North-America.” The quality of her product had been widely acknowledged. Local consumers, according to Broadfield, considered her sturgeon and its associated products “preferable to any manufactured by other persons.” Those products included pickled sturgeon, caviar, glue, oil, and isinglass (a gelatin used in making jellies and glue and for clarifying ale). Yet it was not just customers in the colonies who had recognized the quality of the various commodities she marketed. Broadfield had “obtained the first premium of Fifty Pounds sterling, from the society of arts and commerce in London” for her abilities in “manufacturing sturgeon in the several branches.”

Broadfield was preparing to leave the colonies. She advertised in hopes of finding a successor to take over her business permanently, either a “sober industrious person” or a family whom she could teach “the whole art, secret, and mystery of manufacturing sturgeon in the several branches.” For the moment, however, one of her suppliers, Elijah Bond, carried on her business in addition to operating his own fishery near Trenton. He did so “under the care and inspection of Mrs. BROADFIELD, whose knowledge and experience in that branch of business is well known.” It was Broadfield’s expertise that gave value to the sturgeon products offered for sale, whether purchased from Bond near Trenton or from shopkeepers in Philadelphia. Few advertisements depicted women exercising such authority over male associates in eighteenth-century America, but they were not completely unknown. Broadfield deemed her own skill and reputation the most important elements for selling her products and, ultimately, transferring her business to another entrepreneur.