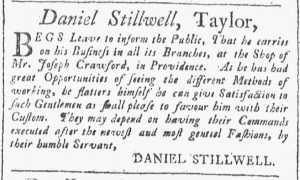

What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“They may depend on having their Commands executed after the newest and most genteel Fashions.”

When Daniel Stillwell, a tailor, placed an advertisement in the June 16, 1770, edition of the Providence Gazette, he made one of the most common and important appeals deployed by colonists who followed his trade. He pledged that clients “may depend on having their Commands executed after the newest and most genteel Fashions.” Tailors and others in the garment trades often made appeals to price, quality, and fashion in their advertisements. Stillwell, like other tailors, believed that price and quality might not have mattered much to those who wished for their clothing to communicate their gentility if their garments, trimmings, and accessories did not actually achieve the desired purpose. Reasonable prices and good quality were no substitute for making the right impression. Stillwell’s work as a tailor required a special kind of expertise beyond measuring, cutting, and sewing. He had to be a keen observer of changing tastes and trends so he could deliver “the newest and most genteel Fashions” to his clients.

To that end, Stillwell informed prospective customers that he “has had great Opportunities of seeing the different Methods of working.” Although he did not elaborate on those experiences, this statement suggested to readers that Stillwell refused to become stagnant in his trade. Rather than learning one method or technique and then relying on it exclusively, he consulted with other tailors and then incorporated new and different techniques, further enhancing his skill. In so doing, he joined the many artisans who asserted that their skill and experience prepared them to “give Satisfaction” to those who employed them or purchased the wares they produced. Stillwell was no novice; instead, he “carries on his Business in all its Branches,” proficiently doing so because of the care he had taken in “seeing the different Methods of working.” Simply observing current fashions was not sufficient for someone in his trade who was unable to replicate them. Stillwell sought to assure prospective clients that he possessed two kinds of knowledge necessary for serving them, a discerning knowledge of the latest styles and a thorough knowledge of the methods of his trade that would allow him to outfit customers accordingly.