GUEST CURATOR: Chloe Amour

What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“LADIES Hair is dressed in different Manners.”

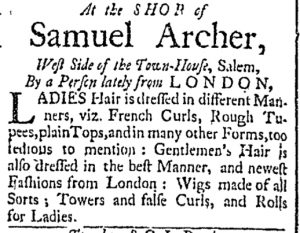

On February 28, 1769, Samuel Archer advertised his services as a hairdresser for both men and women in the Essex Gazette.

For the men, Archer offered wigs according to the “newest Fashions from London,” especially attractive for “Gentlemen” heavily influenced by their British counterparts. For the “Ladies,” he provided “French Curls,” “Towers and false Curls,” and “Rolls.” For both men and women, fashion played a role in helping to determine status and identity to distinguish among social groups. In “Fashion and the Culture Wars of Revolutionary Philadelphia,” Kate Haulman explains that fashion was “dictated for some colonists by Europe” and “indicated commercial and cultural inclusion in a far wide, cosmopolitan Atlantic world. It suggested connection and distinction, proving essential to expressions of rank and power dependent on performing one’s place in the British Empire.”[1] The British identity important to American colonists was reflected in the sorts of fashion, goods, and styles that were part of their lifestyles, including the hairstyles created at Samuel Archer’s shop.

**********

ADDITIONAL COMMENTARY: Carl Robert Keyes

Samuel Archer proclaimed that the ladies of Salem could visit his shop to have their hair “dressed in different Manners.” He listed a few of the most popular styles, but, like many shopkeepers who listed their wares in their advertisements, he insisted that he had not exhausted the possibilities. There were so many “other Forms” that it was “too tedious to mention” them all. Prospective clients could depend on Archer dressing their hair in practically any manner they desired.

Among the styles that he did include, the hairdresser decided to conclude with “Rolls for Ladies,” perhaps hoping to create a lasting impression by ending with one of the most popular styles adopted by women who wished to assert their status. Kate Haulman relates a description of a high roll taken from the diary of Anna Green Winslow of Boston: “red Cow Tail … horsehair … & a little human hair … all carded together and twisted up.” The roll was often decorated with pearls and flowers. A side curl brought down over one shoulder completed the look, which could take hours to create. As Haulman explains, “The amount of time involved in achieving the elaborate look meant that wearing a high roll signified high social status in two ways: by replicating a style worn at court and the beau monde in England and by requiring plenty of spare time to have it constructed.”[2]

The amount of time that hairdressers spent with their clients, particularly clients of the opposite sex, caused some concern, not unlike the uneasiness sometimes directed at dancing masters. “Anxieties over relationships between men and women of different ranks, the potentially illicit exchanges that were occurring, and the social dependency of women with means on men without informed attacks on hairdressers and their clients,” according to Haulman.[3] Although not genteel themselves, hairdressers assisted their clients in crafting appearances that testified to their gentility, thus inverting the usual positions of authority by conferring power on those who earned their livelihood by providing a service rather than those who purchased the service. As Chloe indicates in her analysis of Archer’s advertisement, hairdressers marketed status. Their efforts to do so, however, were fraught with other challenges.

**********

[1] Kate Haulman, “Fashion and the Culture Wars of Revolutionary Philadelphia,” William and Mary Quarterly, 3rd ser., 62, no. 4 (October 2005): 627.

[2] Haulman, 639.

[3] Haulman, 639.