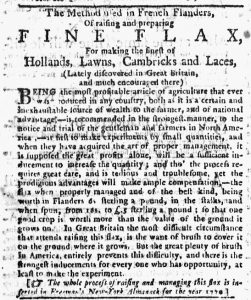

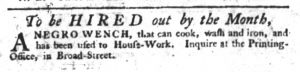

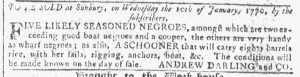

What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

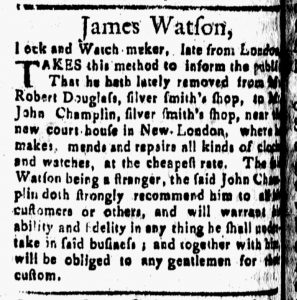

“Many Years experience in the most eminent Shops in London.”

As 1769 drew to a close, the residents of Boston and many other cities and towns throughout the colonies were still embroiled in a dispute with Parliament over the duties imposed on imported paper, glass, lead, paint, and tea by the Townshend Acts. Merchants and shopkeepers continued to participate in nonimportation agreements, refusing to order merchandise of all sorts as a means of using economic pressure to achieve political goals. Especially in Boston, newspapers provided updates about traders who either declined to sign or subsequently violated the boycotts. Discourse about the virtues and vices inherent in making or abstaining from certain purchases became a regular feature in the public prints, in advertisements as well as in editorials.

Yet colonists in Boston and other places did not abstain from all things associated with Britain even as they rejected imported goods. They still looked across the Atlantic, especially to London, for cues about fashion. Colonists continued to imbibe British culture and tastes even as they eschewed British goods. Timothy Kelly, “Hair Cutter and Peruke-Maker from LONDON,” depended on that continued allegiance to British styles in his advertisement that ran in the December 25, 1769, edition of the Massachusetts Gazette and Boston Post-Boy. This wigmaker leveraged his previous experience serving clients in the most cosmopolitan city in the empire, underscoring to the “GENTLEMEN and LADIES” that he “had the advantage of many Years experience in the most eminent Shops in London.” That alone gave his perukes and other hairpieces cachet not associated with wigs made or styled by competitors whose training and entire careers had been confined to the colonies. Kelly claimed he possessed knowledge of the current styles in London, vowing that he made “any kind Perukes now in fashion” and did so “as genteel as can be had from thence.” Why should colonists import wigs from afar when they could consult with an “eminent” stylist in Boston? After all, this stylist was so eminent that he deployed solely his last name as the headline of his advertisement, expecting that to sufficiently identify him when prospective clients perused the newspaper. Kelly did far more than merely promise that he “dresses Hair in any form in the neatest manner” in his advertisement. He accentuated his connections to London and the fashions there, anticipating that doing so would resonate with residents of Boston even as they continued to boycott goods imported from England. British fashions could still be replicated in the colonies, and Kelly offered his services.