What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago this week?

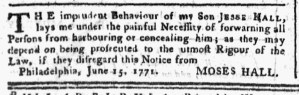

“THE imprudent Behaviour of my Son JESSE HALL, lays me under the painful Necessity of forwarning all Persons from harbouring or concealing him.”

Conradt Wolff lamented that his wife, Jenny, “hath behaved herself in such a manner as lays me under a necessity of forbidding any persons from trusting her on my account.” In an advertisement in the July 1, 1771, edition of the New-York Gazette and Weekly Mercury, he warned the public that he “will pay no debts of her contracting.” Throughout the colonies, similar notices frequently ran in eighteenth-century newspapers. Aggrieved husbands deployed “runaway wife” advertisements to discipline disobedient women, though their notices told only one side of a story of marital discord. Relatively few wives possessed the resources to respond in print. Those that did usually provided much different narratives, often accusing their husbands of abuse and neglect. From their perspective, running away was an act of self-preservation and principled resistance rather than willful disobedience.

On occasion, colonists resorted to the public prints in the wake of other sorts of tumult within their households. On the same day that Wolff placed an advertisement in the New-York Gazette, Moses Hall placed his own notice in the Pennsylvania Chronicle. Hall, however, deplored the misbehavior of his son, Jesse. “THE imprudent Behaviour of my Son,” Hall declared, “lays me under the painful Necessity of forwarning all Persons from harbouring or concealing him.” Furthermore, “they may depend on being prosecuted to the utmost Rigour of the Law, if they disregard this Notice.” Hall did not elaborate on his son’s “imprudent Behaviour,” though gossip and rumors likely circulated beyond the newspaper. That was almost certainly the case for the Camps and the Brents in Elizabethtown, New Jersey. John D. Camp, Jr., informed readers of the New-York Gazette that he had been “compel’d by David Brent, to marry Catherine, his daughter.” Camp vowed to “allow her a separate Maintenance, in all Respects suitable to her Degree,” but he would not pay “any Debts of her Contracting.” Camp carefully avoided the details about events that resulted in his unwelcome wedding. If friends and acquaintances had not been discussing whatever transpired between John and Catherine and her father before the advertisement ran in the New-York Gazette, its appearance probably prompted them to share what they knew for certain and speculate on what they did not.

Wolff, Hall, and Camp all attempted to focus attention on the subjects of their advertisements: an absent wife, a troublesome son, or an imperious father-in-law. In even publishing their notices, however, they called attention to themselves and their shortcomings in maintaining order within their households. They sought to regain authority through the power of the press, but in the process they made their private altercations all the more visible to the public. They framed the narratives and obscured the details, yet they still alerted others to scenes of difficulty and embarrassment that did not reflect well on them despite their efforts to shift responsibility to the actions of others.