What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

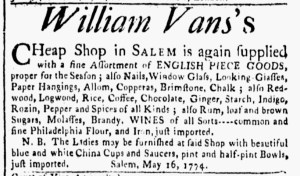

“William Vans’s CHeap Shop.”

Readers encountered several invitations to purchase cheap goods when they perused the May 17, 1774, edition of the Essex Gazette. Stephen Higginson’s advertisement listing dozens of items available “At his Store opposite the King’s Arms in SALEM” featured a headline that proclaimed, “Very Cheap.” That framed how he wished prospective customers to think about his merchandise before they engaged with the rest of his notice. Nathaniel Sparhawk stocked a “large and beautiful Assortment of English, India and European GOODS … at his CHEAP STORE in King-Street, SALEM.” He pledged to sell “at the lowest Advance” or lowest markup “for Cash.” Similarly, William Vans described his establishment as a “CHeap Shop,” though he did not offer further commentary on his prices.

These merchants and shopkeepers deployed the word “cheap” in a different manner than retailers and consumers use it today. For colonizers, “cheap” did not have connotations of inferior quality. Vans certainly did not want prospective customers to think of the “beautiful blue and white China Cups and Saucers” he stocked at his “CHeap Shop” as deficient in any way, nor did Higginson intend for the public to have the impression that he prioritized price over quality for his “Very Cheap” textiles, “Men’s, Women’s and Children’s colour’d and white lamb and kid Gloves,” “Looking-Glasses,” and other wares. Instead, “cheap” merely meant inexpensive. Shoppers could expect to find bargain prices when they went to Vans’s “CHeap Shop” or Sparkawk’s “CHEAP STORE.” The Oxford English Dictionary makes a distinction between “cheap” (meaning “bought at small cost; bearing a relatively low price; inexpensive”) and “cheap and nasty” (meaning “of low price and bad quality; inexpensive but with the disadvantage of being unsuitable to one’s purposes”). The earliest examples for “cheap and nasty” given by the Oxford English Dictionary” come from the 1820s, a half century after Higginson, Sparhawk, Vans, and other advertisers used “cheap” to promote their goods. At the time that colonial entrepreneurs used the word, neither they nor their prospective customers associated “cheap” with poor quality. That sense of the word evolved over time, making it less positive and less powerful in modern marketing campaigns. Today, consumers are wary of cheap goods, but that was not the case in eighteenth-century America.