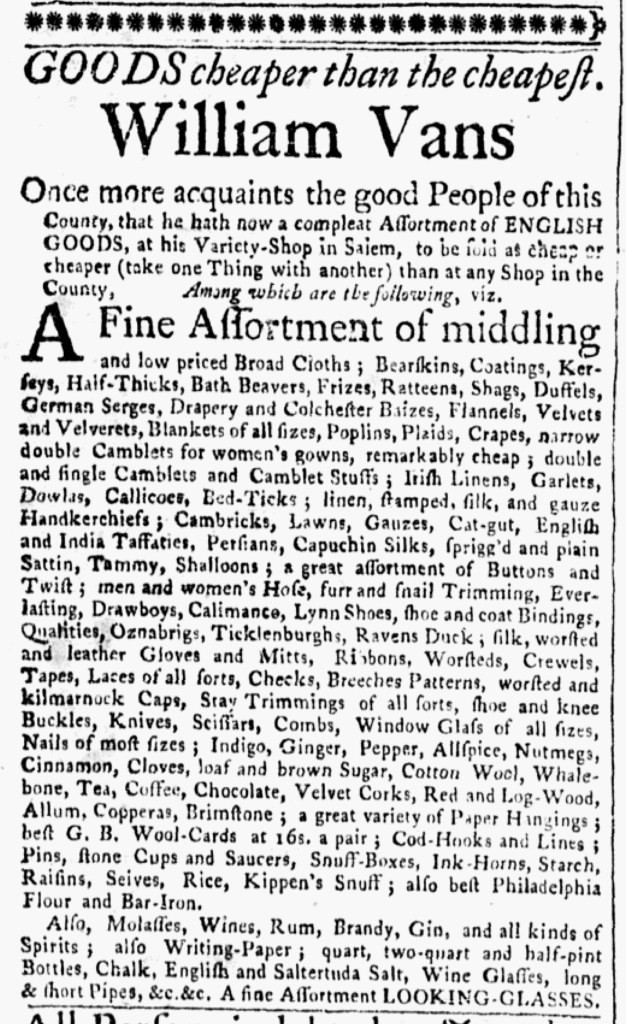

What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

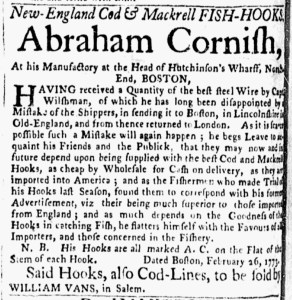

“Said Hooks, also Cod-Lines, to be sold by WILLIAM VANS, in Salem.”

In the early 1770s, Abraham Cornish made “New-England Cod & Mackrell FISH-HOOKS … At his Manufactory” in Boston’s North End. To promote his product, he placed advertisements in the Massachusetts Spy, printed in Boston, and in the Essex Gazette, printed in Salem in March and April 1773, hoping to capture the attention of fishermen in both maritime communities. He presented his hooks as an alternative to those imported to the colonies, describing them as “the best Cod and Mackrell Hooks,” yet he did not ask prospective buyers to take his word for it. Instead, he declared that “Fishermen who made Trial of his Hooks last Season, found them to correspond with his former Advertisement” in which he presented his hooks as “much superior to those imported from England.”

Cornish did not address solely the fisherman who would use his hooks. He also called on those who supplied them to stock his hooks made in Boston in addition to those they acquired from England. He set prices “as cheap by Wholesale for Cash on delivery” as imported hooks, hoping that the combination of price and quality would prompt retailers to add them to their inventory. Cornish believed that various members of the community should demonstrate their interest in supporting the production of fish hooks in Boston, calling on “all Importers, and those concerned in the Fishery” to purchase his product. To cultivate brand recognition, he noted that his hooks “are all marked A.C. on the Flat of the Stem of each Hook.” In an earlier advertisement, he also noted that he packaged them in “paper … marked ABRHAM CORNISH” and called attention to his initials on each hook in order to “prevent deception” or counterfeit products.

To aid in distributing his wares, Cornish recruited a local agent in Salem. His advertisement in the Essex Gazette stated that William Vans, a merchant who frequently placed his own advertisements, sold “Said Hooks.” Vans, however, did not generate the copy for the notice about Cornish’s hooks. The text replicated what appeared in the advertisement in the Massachusetts Spy, with the addition of a nota bene about the marks on each hook and an additional sentence identifying Vans as the local distributor. The version in the Essex Gazette lacked the characteristic woodcut depicting a fish that adorned Cornish’s advertisements in the Massachusetts Spy. Like most other advertisers who incorporated visuals images, Cornish apparently invested in only one woodcut. He depended on the strength of the advertising copy when hawking his hooks in a second market.