What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“Certificates of its success shall be speedily inserted in this and the other Papers on the continent.”

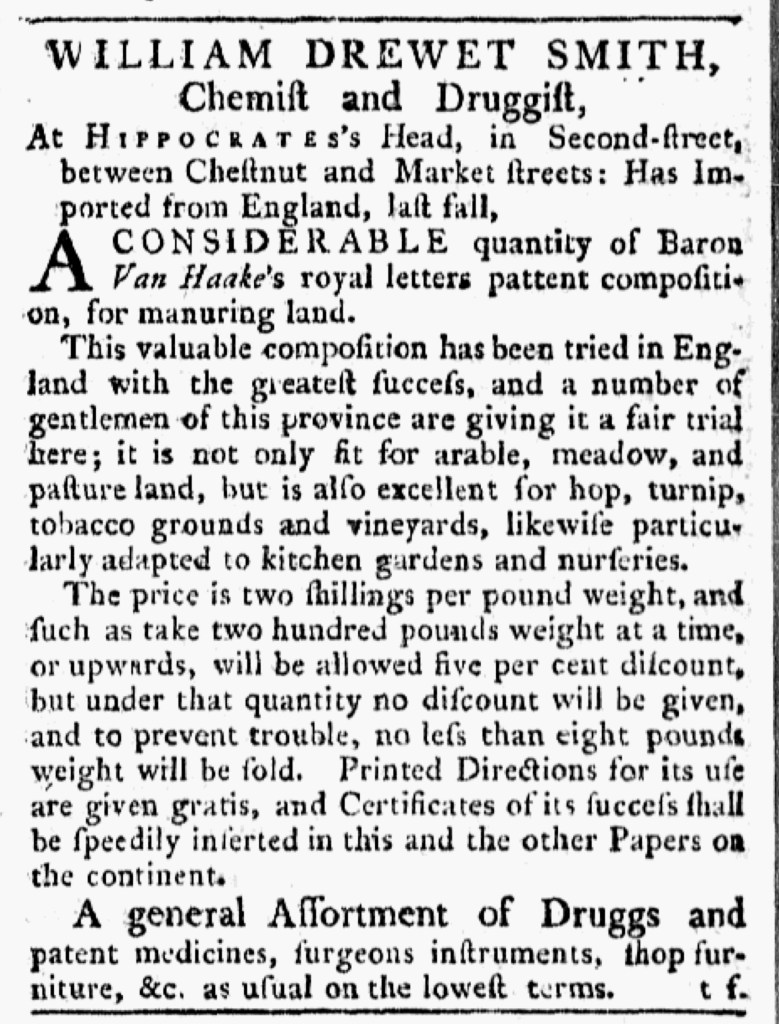

William Drewet Smith, “Chemist and Druggist,” ran an apothecary shop “At HIPPOCRATES’s Head, in Second-street” in Philadelphia in the 1770s. He expected that prospective customers would associate Hippocrates, the ancient Greek physician known as the “Father of Medicine,” with the “general Assortment of Drugs and patent medicines, surgeons instruments, [and] shop furniture” that he sold. Yet those were not the only items that Smith peddled.

The apothecary ran an advertisement for “Baron Van Haake’s royal letter pattent composition, for manuring land” in the March 25, 1775, edition of the Pennsylvania Ledger. In addition to medicines for treating the body, the Smith sold this compound for nurturing soil and raising crops. For those not familiar with its use, the chemist explained that the “valuable composition has been tried in England with the greatest success.” In addition, “a number of gentlemen of this province are giving it a fair trial here.” Trials demonstrated that the treatment “is not only fit for arable, meadow, and pasture land, but is also excellent for hop, turnip, tobacco grounds and vineyards” as well as “kitchen gardens and nurseries.” In other words, any farmer, any gardener, or anybody else who raised crops or plants of any kind needed to try Varon Van Haake’s composition to see for themselves its positive impact on their endeavors.

Smith stated that he included “printed Directions for its use” free with every sale. He also planned to insert “Certificates of its success” (or testimonials from satisfied customers) “in this and the other Papers on the continent,” suggesting that he was already in possession of such endorsements. To further entice prospective customers, he offered a “five per cent discount” to customers who “take two hundred pounds weight at a time, or upwards.” He also mentioned that he imported this product from England “last fall,” signaling to readers that he acquired it before the Continental Association went into effect so they could purchase it with a clear conscience.

Elsewhere in the same issue of the Pennsylvania Ledger, Smith published a lengthy advertisement for “Baron SCHOMBERG’s Grand Prophylactic LINIMENT” that supposedly prevented and cured “most venerial complaints.” He included a statement from the “ingenious” chemist responsible for the liniment and noted that he provided printed directions “for its particular use.” When it came to advertising Baron Van Haake’s composition for treating soil, Smith applied marketing strategies already familiar from the patent medicines that he sold.