What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“A NEAT Mezzotinto print of the Hon. JOHN HANCOCK.”

“A large and exact VIEW of the late BATTLE at CHARLESTOWN.”

“An accurate map of the present seat of CIVIL WAR.”

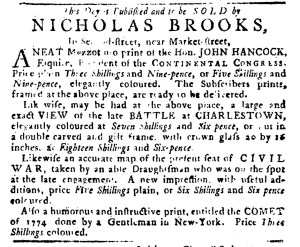

Nicholas Brooks produced and marketed items that commemorated the American Revolution before the colonies declared independence. In an advertisement in the November 1, 1775, edition of the Pennsylvania Journal, for instance, he packaged together three prints previously advertised separately, each of them related to imperial crisis that had boiled over into a war. For this notice, Brooks presented them as a collection of prints for consumers who wished to demonstrate their support for the American cause by purchasing and displaying one or more of them.

Brooks announced that a “NEAT Mezzotinto print of the Hon JOHN HANCOCK, Esquire, President of the CONTINENTAL CONGRESS,” that had previously been proposed in other advertisements had been published and was now for sale at his shop on Second Street in Philadelphia. The subscribers who had reserved copies in advance could pick up their framed copies or arrange for delivery. Others who had not placed advanced orders could acquire the print for three shillings and nine pence or pay two extra shillings for one “elegantly coloured.”

“Likewise, may be had at the above place,” Brooks reported, “a large and exact VIEW of the late BATTLE at CHARLESTOWN,” depicting what has become known as the Battle of Bunker Hill. This print competed with an imitation bearing a similar title, “a neat and correct VIEW of the late BATTLE at CHARLESTOWN,” that Robert Aitken inserted in the Pennsylvania Magazine and sold separately. Brooks, who had long experience selling framed prints, offered choices for his “exact VIEW.” Customers could opt for an “elegantly coloured” version for seven shillings and six pence” or have it “put in a double carved and gilt frame, with glass 20 by 16 inches,” for eighteen shillings and six pence. The eleven shillings for the frame, half again the cost of the print, indicated that Brooks anticipated that customers would display the “exact VIEW” proudly in their homes or offices.

He also promoted “an accurate map of the present seat of CIVIL WAR, taken by an able Draughtsman,” Bernard Romans, “who was on the spot of the late engagement.” Brooks revised copy from earlier advertisements: “The draught was taken by the most skillful draughtsman in all America, and who was on the spot at the engagements of Lexington and Bunker’s Hill.” The map showed a portion of New England that included Boston, Salem, Providence, and Worcester. This print, he declared, was a “new impression, with useful additions,” though he did not specify how it differed from the one he previously marketed and sold. As with the others, customers had a choice of a plain version for five shillings or a “coloured” one for six shillings and six pence.

Brooks added one more item, “a humorous and instructive print, entitled the COMET of 1774, done by a Gentleman in New-York.” Did this print offer some sort of satirical commentary on current events? Or was it unrelated to the prints of Hancock, the Battle of Bunker Hill, and the “CIVIL WAR” in New England? Whatever the additional print depicted, Brooks made the prints that commemorated the American Revolution the focus of his advertisement, gathering together three items previously promoted individually. In so doing, he not only offered each print to customers as separate purchases but also suggested that they could consider them part of a collection. Consumers who really wanted to demonstrate their patriotism could easily acquire all three at his shop.

[…] Nicholas Brooks produced and marketed items that commemorated the American Revolution before the colonies declared independence. In an advertisement in the November 1, 1775, edition of the Pennsylvania Journal, for instance, he packaged together three prints previously advertised separately, each of them related to imperial crisis that had boiled over into a war. For this notice, Brooks presented them as a collection of prints for consumers who wished to demonstrate their support for the American cause by purchasing and displaying one or more of them. Read […]