What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“To be SOLD … THE estate of John Randolph, esq; his majesty’s attorney-general.”

The advertisement for the “Estate of John Randolph” that ran in John Dixon and William Hunter’s Virginia Gazette in the fall of 1775 also appeared in the other newspapers published in Williamsburg, John Pinkney’s Virginia Gazette and Alexander Purdie’s Virginia Gazette. When the Loyalist departed for England, either he left instructions to advertise widely or the trustees – Peyton Randolph (his brother), John Blair, and James Cocke – decided that they wanted news of the upcoming sale of Randolph’s house, furniture, and enslaved “family servants” to circulate as widely as possible.

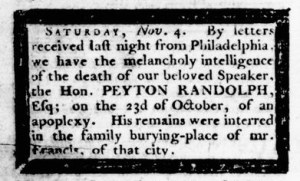

When the advertisement ran on the final page in the November 3 edition of Purdie’s Virginia Gazette, it contradicted news that appeared on the second page. Thick black borders that indicated mourning surrounded a short article that informed readers, “By letter received last night from Philadelphia, we have the melancholy intelligence of the death of our beloved Speaker, the Hon. PEYTON RANDOLPH, Esq; on the 23d of October, of an apoplexy. His remains were interred in the family burying-place of mr. Francis, of that city.” Randolph had served as speaker of the colony’s House of Burgesses. He also held very different political views than his brother, having served as president of the First Continental Congress when it met in Philadelphia in the fall of 1774 and, briefly, as president of the Second Continental Congress when it convened after the battles at Lexington and Concord the following year. He had been in Philadelphia as one of Virginia’s delegates when he died.

Blair and Cocke, the “surviving trustees,” ran an updated advertisement the following week, but there had not been time to revise the notice that had been running for several weeks. The side of the broadsheet that carried the advertisement may even have been printed already when Purdie’s printing office received word of Randolph’s death. In addition, the report, dated “SATURDAY, Nov. 4,” introduces some confusion about when the news arrived and when Purdie printed and distributed the November 3 edition of his newspaper. Purdie scooped the other two newspapers. Pinkney delivered the news in his next edition on November 9 (along with the updated advertisement). Dixon and Hunter inserted a news report and an extensive memorial on November 11. Either they did not have the news in time for their November 4 edition, or the type had been set and the printing already commenced when it arrived. That still does not describe the discrepancy in the dates for Purdie’s newspaper, though he may have been a day late in publishing it but listed November 3, the anticipated date of publication for the weekly newspaper, in the masthead as a polite fiction.

Not only did Purdie publish the news first with a brief article, but the following week he ran both a news article about Randolph’s death and funeral and a memorial to Randolph in his November 10 edition. The text matched the memorial in Dixon and Hunter’s November 11 edition, but the compositor made different choices for the format. Purdie also honored Randolph with thick black borders around the content on all four pages, not just enclosing the memorial. That issue included the updated notice about John Randolph’s estate sale as the first of the advertisements on the final page, though the two-page supplement that accompanied it carried the original advertisement. The news and an advertisement continued delivering contradictory information, suggesting that Purdie and others in his printing office were not attentive to every detail in every advertisement they published. The original advertisement may have appeared again as filler to complete the page rather than as an intentional insertion by the trustees who oversaw the sale it announced.

[…] Upon learning of the death of Peyton Randolph, one of the original trustees, they had updated an advertisement that had been running in that newspaper as well as John Pinkney’s Virginia Gazette and John Dixon and William Hunter’s Virginia Gazette […]

[…] The advertisement for the “Estate of John Randolph” that ran in John Dixon and William Hunter’s Virginia Gazette in the fall of 1775 also appeared in the other newspapers published in Williamsburg, John Pinkney’s Virginia Gazette and Alexander Purdie’s Virginia Gazette. When the Loyalist departed for England, either he left instructions to advertise widely or the trustees – Peyton Randolph (his brother), John Blair, and James Cocke – decided that they wanted news of the upcoming sale of Randolph’s house, furniture, and enslaved “family servants” to circulate as widely as possible. Read […]