What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“RESOLVED, That we abhor the enslaving of any of the human race, and particularly of the NEGROES in this county.”

Nathaniel Read’s advertisement describing Tower, an enslaved man who liberated himself by running away, and offering a reward for his capture and return ran in the Massachusetts Spy a second time on June 21, 1775. It was the last time that advertisement appeared. Perhaps the notice achieved its intended purpose when someone recognized the Black man with “a little scar on one side [of] his cheek” or perhaps Read discontinued it for other reasons.

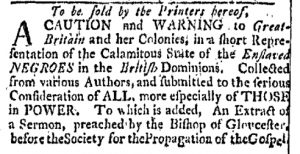

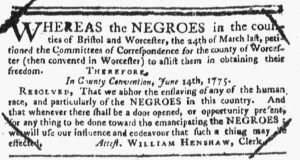

Whatever the explanation, Read’s advertisement starkly contrasted with a new notice that relayed a resolution passed “In County Convention” on June 14.[1] “[T]he NEGROES in the counties of Bristol and Worcester, the 24th of March last, petitioned the Committees of Correspondence for the county of Worcester (then convened in Worcester) to assist them in obtaining their freedom.” As the imperial crisis intensified and colonizers invoked the language of liberty and freedom from (figurative) enslavement, Black people who were (literally) enslaved in Massachusetts applied that rhetoric to themselves and initiated a process that challenged white colonizers to recognize their rights. They did so before the Revolutionary War began with the battles at Lexington and Concord in April 1775, though it took a few months for the County Convention to pass a resolution. That resolution supported the petition: “we abhor the enslaving of any of the human race, and particularly of the NEGROES in this county.” Furthermore, “whenever there shall be a door opened, or opportunity present, for any thing to be done toward the emancipating the NEGROES; we will use our influence and endeavour that such a thing may be effected.”

During the era of the American Revolution, the press often advanced purposes that seem contradictory to modern readers. Newspapers undoubtedly served as engines of liberty that promoted the American cause and shaped public opinion in favor of declaring independence, yet they also played a significant role in perpetuating the enslavement of Africans, African Americans, and Indigenous Americans. News articles reported on the dangers posed by enslaved people, especially when they engaged in resistance or rebellion, and advertisements facilitated the slave trade and encouraged the surveillance of Black men and women to determine whether they matched the descriptions of enslaved people who liberated themselves. Revenue from those advertisements underwrote publishing news and editorials that supported the patriot cause. Yet the early American press occasionally published items that supported the emancipation of enslaved people and abolishing the transatlantic slave trade as some colonizers applied the rhetoric of the American Revolution more evenly to all people.

**********

[1] Although it resembles a news article, this item appeared among the advertisements. In addition, it ran more than once, typical of paid notices rather than news printed just once. Newspaper advertisements often delivered news, especially local news, during the era of the American Revolution.