What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

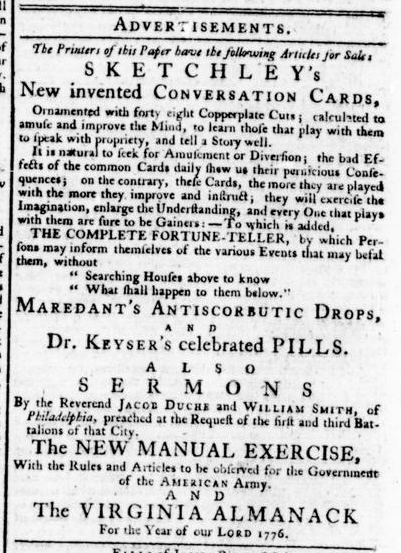

“SKETCHLEY’s New Invented CONVERSATION CARDS.”

Like other newspaper printers, John Dixon and William Hunter provided a variety of goods and services to supplement the revenues from subscriptions and advertisements. The masthead of the Virginia Gazette solicited customers for “Printing Work done at this Office in the neatest Manner, with Care and Expedition.” In addition to job printing, they also published books, pamphlets, and almanacs and, according to their advertisement in the October 28, 1775, edition, they even sold patent medicines. Many colonial printers kept a stock of similar “MAREDANT’S ANTISCORBUTIC DROPS” and “Dr. KEYSER’S celebrated PILLS” on hand, promoting them in their own newspapers.

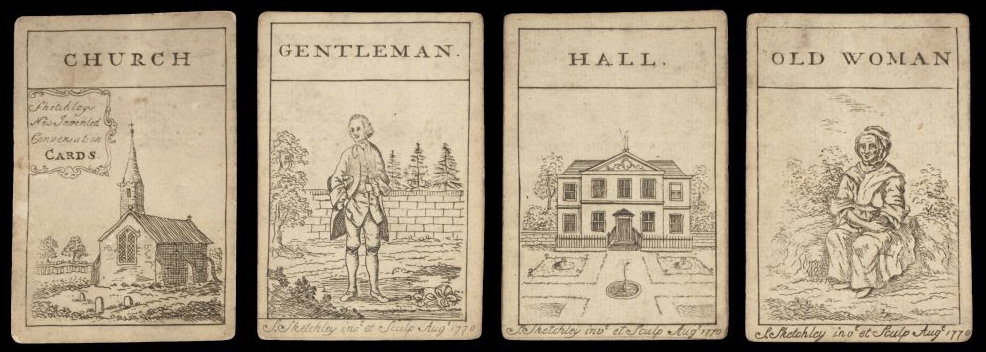

Hawking yet another product accounted for nearly half of Dixon and Hunter’s advertisement in that issue of the Virginia Gazette: “SKETCHLEY’s New invented CONVERSATION CARDS, Ornamented with forty eight Copperplate Cuts.” Today, conversation cards serve a variety of purposes. They can be used for icebreakers at social gatherings, teambuilding exercises for businesses and organizations, or discussion starters among people seeking to explore topics of common interest and forge stronger personal connections. While consumers may have used Sketchley’s conversation cards in a variety of ways, the advertisement stated that they were “calculated to amuse and improve the Mind, to learn those that play with them to speak with propriety, and tell a Story well.” In that regard, these cards differed from playing cards for popular games of “Amusement and Diversion” and the “bad Effects of the common Cards” that “daily show us their pernicious Consequences.” Card games did not have to devolve to the vices of too much luxury and leisure, too much gossip and idle chatter, and too much drinking and gambling. Sketchley’s conversation cards, “on the contrary, … the more they are played with the more they improve and instruct; they will exercise the Imagination, enlarge the Understanding, and every One that plays with them are sure to be the Gainers.” In the company of friends, those who used the cards would become more articulate in their speech, more refined in their comportment, and more enlightened in their understanding of the world.

What did consumers acquire when they purchased their own deck of Sketchley’s conversation cards? Dominic Winter Auctioneers offer this description: “copper engraved playing cards,” measuring 3.75 inches by 2.5 inches, “each with a word [in the] upper margin and [the] associated illustration below.” The partial set that the auctioneers offered for bids included seventeen cards, such as “Hope,” “Honour,” “Heart,” and “Ruin.” According to the online auction catalog, those are the only cards from this set known to survive. “The only other similar, but not identical, set we have been able to trace,” the catalog states, “is that held by the Osborne Collection …, which comprises 52 cards.” It also features images of sixteen of the cards. In addition, the catalog notes the advertisement in the Virginia Gazette. Like most shop signs and many book catalogs, early American newspaper advertisements reveal details that otherwise have been lost because the artifacts do not survive.

By the time that James Sketchley first marketed his “New invented CONVERSATION CARDS” in 1770, he had been producing playing cards for about two decades. With these cards, he offered an alternative to games of leisure that passed the time with little else to show for it, just as John Ryland had done with a set of “Geographical Cards” that Nichols Brooks advertised in the Pennsylvania Journal in March 1773. Dixon and Hunter prompted genteel readers and those who aspired to gentility to consider these conversation cards a valuable resource to purchase when their bought they almanac for the coming year or a military manual that included “the Rules and Articles to be observed for the Government of the AMERICAN Army.”