What kinds of advertisements ran in the inaugural issue of Alexander Purdie’s Virginia Gazette 250 years ago today?

“BENJAMIN BUCKTROUT, Cabinet maker, … STILL carries on that business.”

“To be sold … THIRTY Virginia born negroes, consisting of men, women, boys, and girls.”

Alexander Purdie launched his Virginia Gazette on Friday, February 3, 1775. It was the third newspaper bearing that name printed in Williamsburg at the time. John Pinkney published his Virginia Gazette on Thursdays and John Dixon and William Hunter distributed their Virginia Gazette on Saturdays. As the imperial crisis intensified, a third Virginia Gazetteincreased access and dissemination of news and editorials (and advertisements) in the colony.

In early December 1774, Purdie and Dixon announced the dissolution of their partnership, with Dixon indicating that he would continue to publish that iteration of the Virginia Gazette with Hunter as his new partner and Purdie asserting that he would commence publication of another newspaper as soon as he attracted a sufficient number of subscribers. He also solicited advertisers, realizing that paid notices accounted for an important source of revenue for any newspaper.

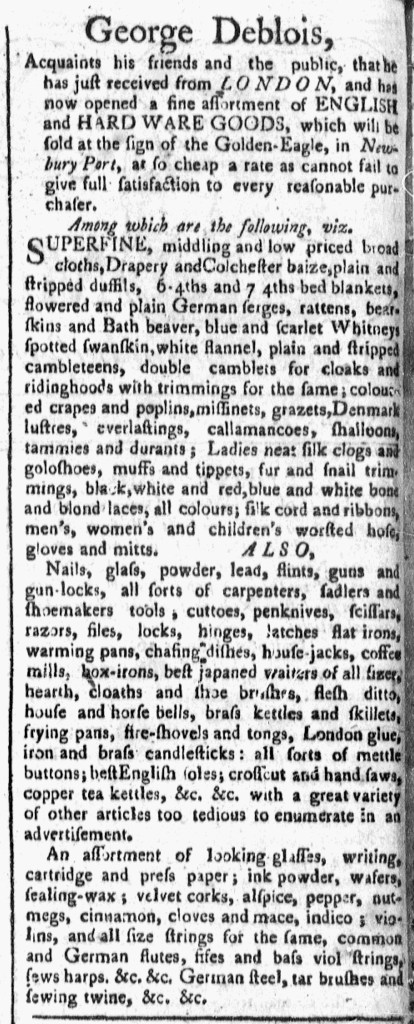

When he published the inaugural issue of his Virginia Gazette, it included seven advertisements that filled most of the last column on the final page. Those numbers did not rival the amount of advertising in either of the other newspapers printed in Williamsburg that week, both of which had enough notices to fill an entire page, but it was a start. Those initial advertisers signaled to others that they might consider advertising in Purdie’s newspaper a good investment.

Benjamin Bucktrout, a cabinetmaker, did not entrust his marketing efforts solely to Purdie’s Virginia Gazette. He placed an identical advertisement in Dixon and Hunter’s newspaper the next day. It likely enjoyed greater circulation in the more established Virginia Gazette, yet may have garnered greater notice by readers of Purdie’s Virginia Gazette as the first of only a few advertisements in that publication.

In addition to Bucktrout’s notice, one advertisement sought an apprentice to work in a store, two noted stray horses “TAKEN up” until their owners could be identified, and three concerned enslaved people. Abraham Smith and Henry Lochhead presented “THIRTY Virginia born negroes, consisting of men, women, boys, and girls,” for sale. Townshend Dade offered a reward for the capture and return of “a negro fellow named HARRY” who had liberated himself by running away from his enslaver the previous August. Peter Pelham advised readers of “a runaway negro man named Goliah” who had been “COMMITTED to the publick jail” until his enslaver claimed him. Advertisements about enslaved people represented a significant proportion of notices in each Virginia Gazette. They amounted to nearly half of the advertisements in the first issue of Purdie’s Virginia Gazette.