GUEST CURATOR: Gabriela Vargas

What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

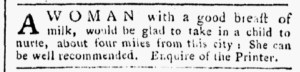

“A WOMAN with a good breast of milk, would be glad to take in a child to nurse.”

On February 20, 1775, an anonymous woman placed an advertisement offering her services as a wet nurse in Dunlap’s Pennsylvania Packet. In colonial and revolutionary America, women advertised their services as wet nurses while families often placed advertisements seeking wet nurses. Mothers who could not supply their own breast milk due to health issues acquired wet nurses. Families who lost mothers during childbirth also needed wet nurses. This was a common practice in the eighteenth century.

According to Janet Golden, some English physicians advised against wet nurses because they might be “sick or ill-tempered.”[1] William Buchan, for instance, advised looking for a “healthy woman, … one with an abundant supply of milk, healthy children, clean habits and a sound temperament.”[2] Those physicians looked down on women not breastfeeding their own children but doing it for others. In general, wet nursing caused an increase in infant mortality rate. Golden states, “Nearly every European commentator knew that wet nursing increased infant mortality. Wet-nursed infants were more likely to die than were infants suckled by their mothers, and the wet nursing system itself contributed to infant mortality by inducing poor women to abandon their own offspring in order to find employment suckling the children of others.”[3]

For women who were hired as wet nurses in colonial America, their earnings belonged to their husbands by law.[4] Wet nursing was not always a paid arrangement. Instead, neighbors sometimes helped their communities by nursing the babies of mothers who could not breastfeed due to postpartum ailments.[5] Some families felt more comfortable with a neighbor rather than a stranger. Mothers or their families would often look for neighbors or friends to breastfeed their babies, but that was not always possible. That created a market for other women to offer their services, which they would advertise in early American newspapers.

**********

ADDITIONAL COMMENTARY: Carl Robert Keyes

Even though the prescriptive literature authored by English physicians sometimes cautioned against entrusting infants to wet nurses, colonizers sometimes heeded those concerns and other times developed their own practices embedded in local circumstances in the eighteenth century. As Gabriela indicates, neighbors participated in communal wet nursing as one way of contributing to their communities.

Some also went against the prescriptive literature that condemned wealthy women for hiring wet nurses instead of fulfilling what the physicians considered their maternal obligations. Sending infants to foster with wet nurses in the countryside became a popular practice among many affluent families in Boston and other cities. “Some urban families,” Golden explains,” assumed that the city was an unhealthy environment, rife with both epidemic and endemic diseases. The countryside, many believed, provided a more salubrious setting, especially in the early months of life.”[6] Note that the anonymous “WOMAN with a good breast of milk” in the advertisement Gabriela selected emphasized that she resided about four miles from Philadelphia, near the busy port yet removed from the largest city in the colonies. Other women took a similar approach. According to Golden, “advertisements placed by women looking for babies to wet nurse reported their distance from the city.”[7]

In four short lines, the woman who placed today’s featured advertisement addressed several common concerns. She commented on her own health and the nourishment she could provide for an infant, asserting that she had a “good breast of milk.” Yet she did not ask prospective clients to take her word for it. Instead, she stated that she “can be well recommended,” presumably both for her character and for her health. At the same time, she testified to the healthiness of the environment where she provided her services, highlighting that she resided outside the city. The anonymous woman intended for each of those appeals to resonate with mothers and their families.

**********

[1] Janet Golden, A Social History of Wet Nursing in America: From Breast to Bottle (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1996), 15.

[2] Golden, Social History of Wet Nursing, 16.

[3] Golden, Social History of Wet Nursing, 14.

[4] Golden, Social History of Wet Nursing, 17.

[5] Golden, Social History of Wet Nursing, 20.

[6] Golden, Social History of Wet Nursing, 22.

[7] Golden, Social History of Wet Nursing, 22.