What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“Advertise the said William Hambleton Scholar as a notorious Cheat.”

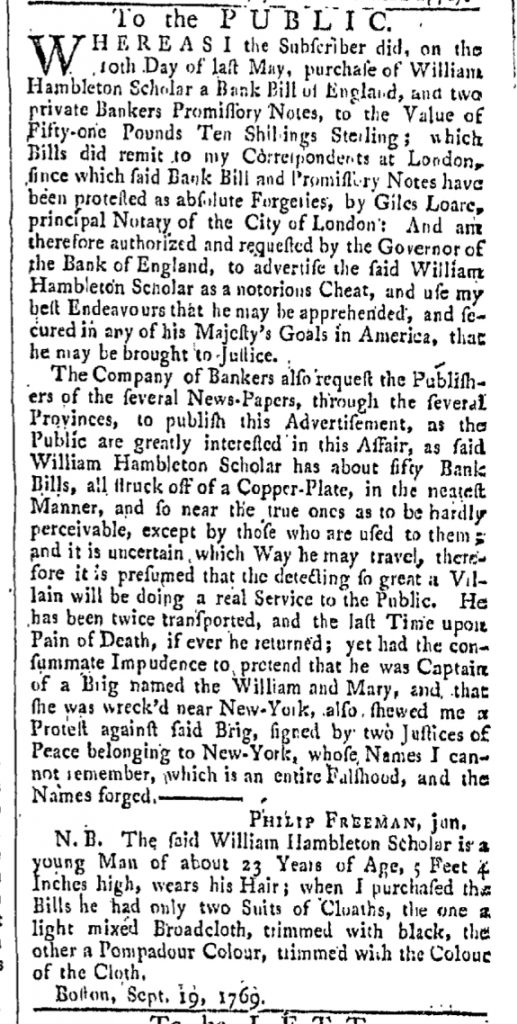

Advertisement or news article? An item that appeared in the September 30, 2019, edition of the Providence Gazette raises interesting questions about its purpose. Extending half a column, it detailed the activities of William Hambleton Scholar, a confidence man who had defrauded Philip Freeman, Jr., of “Fifty-one Pounds Ten Shillings Sterling” through the sale of “a Bank Bill of England, and two private Bankers Promissory Notes.” All three financial devices were forgeries. It took Freeman some time to learn that was the case. He had purchased the bank bill and promissory notes in May and remitted them to associates in London, only to learn several months later that Giles Loare, “principal Notary of the City of London” declared them “absolute Forgeries.”

In response, officials from the Bank of England “authorized and requested” that Freeman “advertise the said William Hambleton Scholar as a notorious cheat.” They instructed Freeman to act on their behalf to encourage the apprehension of the confidence man. To that end, “[t]he Company of Bankers also request the Publishers of the several News-Papers, through the several Provinces, to publish this Advertisement.” Freeman asserted that the public was “greatly interested in this Affair,” but also warned that Scholar had another fifty bank bills “all struck off of a Copper-Plate, in the neatest Manner, and so near the true ones as to be hardly perceivable.” The narrative of misdeeds concluded with a description of the confidence man, intended to help the public more easily recognize him since “it is uncertain which Way he may travel.”

Was this item a paid notice or a news article? Freeman referred to it as an “Advertisement,” but “advertisement” sometimes meant announcement in the eighteenth-century British Atlantic world. It did not necessarily connote that someone paid to have an item inserted in the public prints. The story of Scholar and the forged bank bills appeared almost immediately after news items from New England, though the printer’s advertisement for a journeyman printer appeared between news from Providence and the chronicle of the confidence man’s deception. No paid notices separated the account from the news, yet a paid notice did appear immediately after it. This made it unclear at what point the content of the issue shifted from news to paid notices. The following page featured more news and then about half a dozen paid notices. Perhaps the printer had no expectation of collecting fees for inserting the item in his newspaper, running it as a service to the public. It informed, but also potentially entertained readers who had not been victims of Scholar’s duplicity. That the “Advertisement” interested readers may have been sufficient remuneration for printing it in the Providence Gazette.