What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“Wedding-Cakes.”

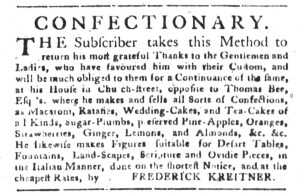

Frederick Kreitner made and sold sweet treats at his “CONFECTIONARY” in Charleston in the early 1770s. In an advertisement in the November 23, 1773, edition of the South-Carolina Gazette and Country Journal, he expressed “his most grateful Thanks to the Gentlemen and Ladies, who have favoured him with their Custom” and solicited the patronage of new and returning customers. The confectioner listed several of the items he made and sold, including macaroons, “Tea-Cakes of all Kinds, Sugar-Plumbs, [and] preserved Pine-Apples, Oranges, Strawberries, Ginger, Lemons, and Almonds.” Kreitner also advertised that he sold “Wedding-Cakes.”

What distinguished a wedding cake from other cakes in colonial Charleston? In “Wedding Cake: A Slice of History,” Carol Wilson examines a variety of traditions, including English traditions that colonizers brought with them to North America. According to Wilson, “bride cake, the predecessor of the modern wedding cake,” replaced bride pie in the seventeenth century. “Fruited cakes, as symbols of fertility and prosperity, gradually became the centerpieces for weddings.” However, a “much less costly bride cake took the simpler form of two large rounds of shortcrust pastry sandwiched together with currants and sprinkled with sugar on the top.” This simple type of cake “could easily be cooked on a bakestone on the hearth.” Wilson also reports, “Bride cake covered with white icing first appeared sometime in the seventeenth century.” In 1769, Elizabeth Raffald, known for the recipes and other household hints she published in England, “was the first to offer the combination of bride cake, almond cake, and royal icing.” In 1773, Raffald published the third edition of The Experienced English Housekeeper, for the Use and Ease of Ladies, Housekeepers, Cooks. It contained nearly nine-hundred recipes, including instructions “To make a BRIDE CAKE,” “To make ALMOND-ICEING for the BRIDE CAKE,” and “To make SUGAR ICEING for the BRIDE CAKE.” Raffald considered these recipes so important that she placed them first in chapter 11, following and introduction that offered “Observations upon CAKES.”

Prospective customers in Charleston had expectations about what distinguished wedding cakes from “Tea-Cakes” and other cakes that Kreitner made and sold. By including wedding cakes among the confections in his advertisement, Kreitner aided in further diffusing traditions associated with new marriages and presented himself as an authority who could assist customers who wished to adhere to contemporary fashions and rituals.