What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“An elegant Edition of the MANUAL EXERCISE [with] the various Positions of a Soldier under Arms.”

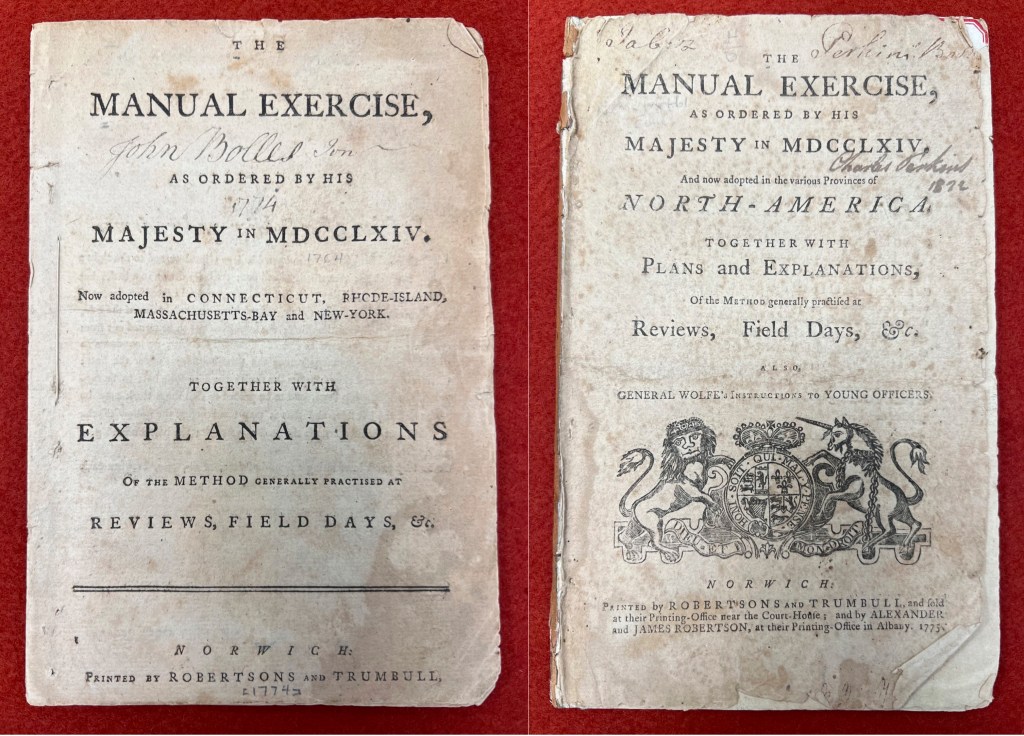

Advertisements for The Manual Exercise as Ordered by His Majesty in 1764: Together with Plans an Explanations of the Method Generally Practised at Reviews and Field-Days appeared in several newspapers printed in New England in 1774, one indication of how colonizers reacted to the trouble brewing with Great Britain. Printers in five towns produced their own editions, including Ezra Lunt and Henry-Walter Tinges in Newburyport, Massachusetts, John Carter in Providence, Rhode Island, Judah Paddock Spooner in Norwich, and Thomas Green and Samuel Green in New Haven, Connecticut. In Boston, Isaiah Thomas printed the book and Thomas Fleet and John Fleet issued three variant editions. They may have also published a previous edition in 1773, based on an inscription that appears in one surviving copy.

In 1775, printers beyond New England produced other editions after the skirmishes at Lexington and Concord and the ensuing military actions. In New York, Hugh Gaine published one edition; another printed by J. Anderson has been dated to that year. William Bradford and Thomas Bradford issued the book in Philadelphia. So did Robert Aitken, meeting with sufficient demand to issue a second edition. Francis Bailey in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, James Adams in Wilmington, Delaware, and John Dixon and William Hunter in Williamsburg, Virginia, each published local editions in 1775.

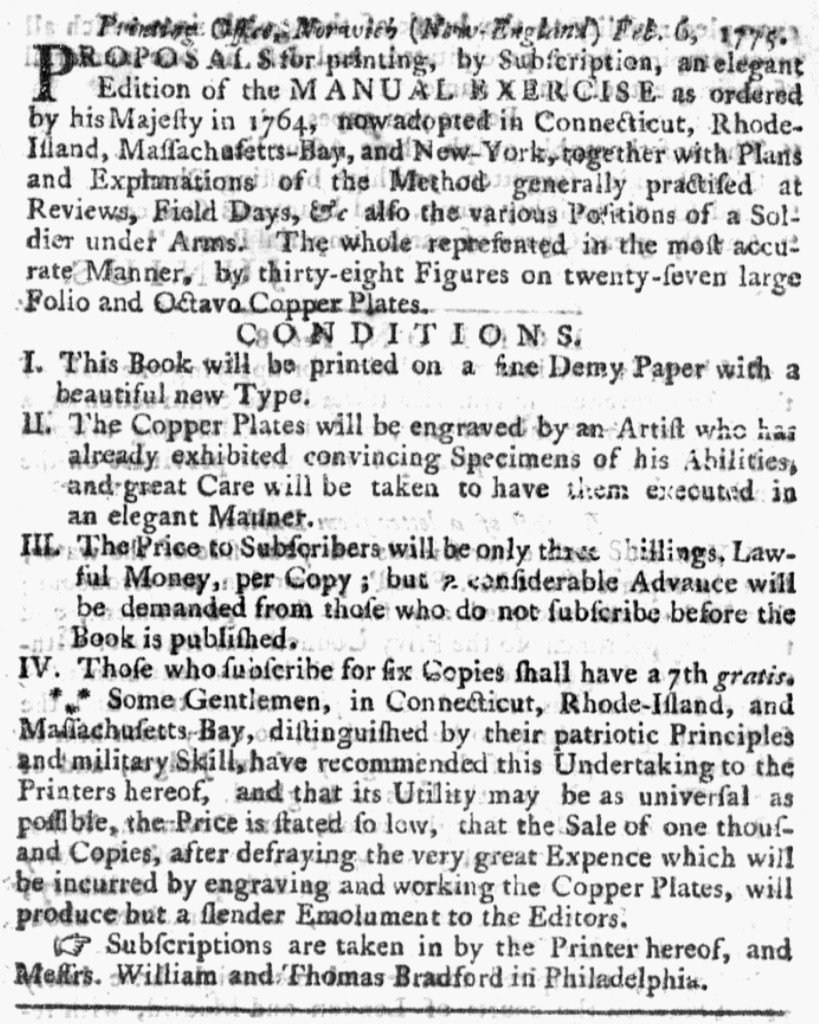

Alexander Robertson, James Robertson, and John Trumbull in Norwich, Connecticut, were among the printers who published an edition in 1774. In the October 13 edition of the Norwich Packet, they advertised that they had “Just published … THE MANUAL EXERCISE, AS ORDERED BY HIS MAJESTY, And now adopted in the Colonies of CONNECTICUT, RHODE-ISLAND, and Province of MASSACHUSETTS-BAY.” On February 23, 1775, they ran much more elaborate subscription proposals for another edition, an “ELEGANT EDITION” that would include “38 Figures on 27 large Folioand Octavo Copper Plates” that depicted the “various POSITIONS of a SOLDIER UNDER ARMS.” They explained that “Some Gentlemen, distinguished by their patriotic Principles and military Skill, have recommended this Undertaking to the Printers” as a service to the public. In the interest of disseminating the book widely so “its Utility may be as universal as possible,” the printers set a low price, “only three Shillings … per Copy” for subscribers who ordered theirs in advance. Those “who do not subscribe before the Book is published,” on the other hand, could expect to pay “a considerable Advance” (or higher price). The Robertsons and Trumbull set the price such that “the Sale of 500 Copies” would defray “the very great Expence which will be incurred by the engraving and working the Copper Plates” and yield “but a slender Emolument to the Editors.”

In those proposals, the printers listed local agents who collected subscriptions in Boston, Chelsea, Newburyport, and Salem in Massachusetts, Portsmouth in New Hampshire, and Providence in Rhode Island. In addition, three post riders also took orders from subscribers. Eventually, a version of the proposals ran in the Pennsylvania Evening Post. It did not include the lengthy list of local agents in New England, but instead specified that Benjamin Towne, the printer of the Pennsylvania Evening Post, and William Bradford and Thomas Bradford, the printers of the Pennsylvania Journal, collected subscriptions in Philadelphia. Perhaps the Bradfords had not yet determined to publish their own edition. Those proposals also doubled the number of subscribers necessary for “defraying the great Expence” of the engravings to one thousand.

Even though the Robertsons and Trumbull promoted the copper plates, asserting that they “will be engraved by an Artists who has already exhibited convincing Specimens of his Abilities, and great Care will be taken to have them executed in an elegant Manner,” they did not include those illustrations with the new edition they published in 1775. That edition closely paralleled their previous edition, though it did have a new title page and “Instructions for young OFFICERS. By GENERAL WOLFE” on the final page, which had been blank in the 1774 edition. While it is possible that the engravings were removed from the copy in the collections of the American Antiquarian Society at some point over the past 250 years, it seems more likely that events overtook the printers. Once the imperial crisis became a war, they may have been less concerned about commissioning copperplate engravings and more interested in issuing a new edition of the Manual Exercise to meet the demand of colonizers who believed more than ever that they needed the instructions in that volume.