What advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“To be sold by the Printers hereof, Mr. Hancock’s ORATION, On the Fifth of March.”

Immediately above the record of ships “Entered-In,” “Outward-Bound,” and “Cleared-Out” from the customs house in Boston in the April 5, 1774, edition of the Essex Gazette, Samuel Hall and Ebenezer Hall, the printers, inserted a brief notice, just three lines, alerting readers that they sold “Mr. Hancock’s ORATION, On the Fifth of March.” The Halls did not need to provide further elaboration for readers to understand the announcement. For colonizers in New England in the 1770s, the phrase “Fifth of March” conjured images like the phrase “Boston Massacre” evokes today. They needed no explanation that the advertisement referred to John Hancock delivering the annual address to commemorate the event, to honor those killed when British soldiers from the 29th Regiment under the command of Captain Thomas Preston fired into a crowd of protesters, to condemn quartering troops in colonial cities during times of peace, and to advocate for American liberties.

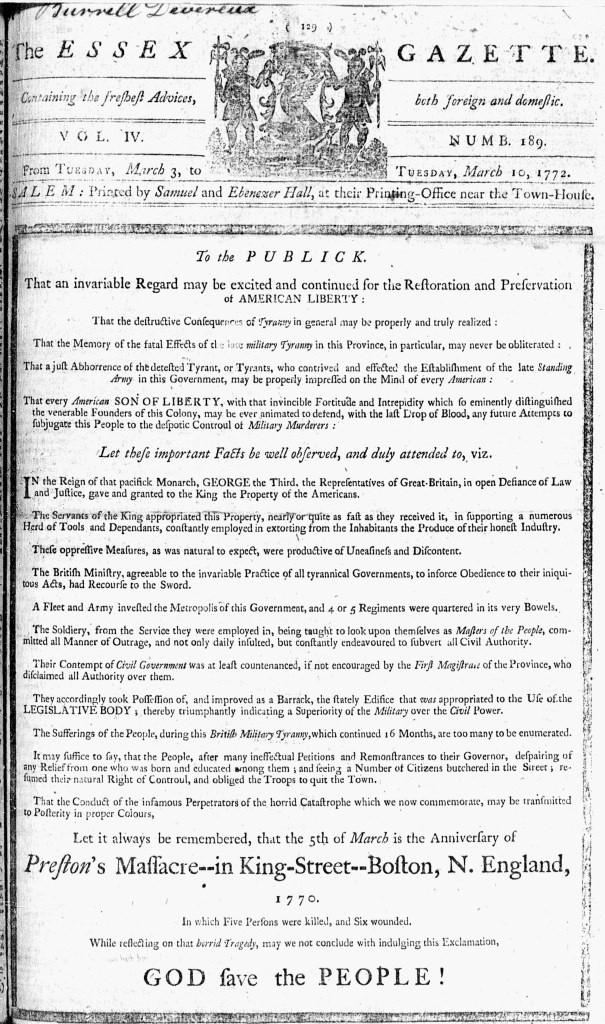

As had become customary by the fourth anniversary of the Boston Massacre, the town voted to have the oration published and advertisements appeared in newspapers printed in Boston. Yet they did not appear solely in newspapers in that town. Other newspapers in New England sometimes carried them as well, none more often that the Essex Gazette, published in nearby Salem. Samuel Hall had a long history of publishing news and opinion that favored sentiments expressed by Patriots. On the first anniversary of the Boston Massacre, for instance, he included thick black mourning borders on the first page of his newspaper and published “a solemn and perpetual MEMORIAL Of the Tyranny of the British Administration of Government in the Years 1768, 1769, and 1770,” especially “THE FIFTH OF MARCH, … the Anniversary of Preston’s Massacre–in King-Street–Boston, N. England–1770.” When Benjamin Edes and John Gill, among the most ardent of Patriots among the printers in Boston, published Hancock’s oration in 1774, the Halls acquired copies to disseminate in Salem and beyond. In so doing, they participated in the commodification of the Boston Massacre while simultaneously commemorating it and encouraging others to side with the Patriots as relations with Parliament further deteriorated following the Boston Tea Party the previous December.