Who was the subject of an advertisement in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

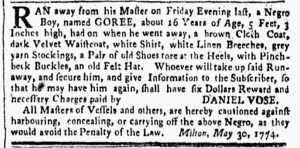

“RAN away … a Negro Boy, named GOREE.”

As the summer of 1774 approached, an enslaved youth named Goree saw his opportunity to liberate himself by running away from Daniel Vose of Milton, Massachusetts. Vose, for his part, joined the ranks of enslavers who placed newspaper advertisement that offered rewards for the capture and return of enslaved men and women who made similar declarations of independence during the era of the American Revolution. He provided a description of the Goree, encouraging readers to engage in surveillance of all Black people, especially young Black men, with the intention that such scrutiny would aid in identifying him. Vose also warned “All Masters of Vessels and others … against harbouring, concealing, or carrying off” Goree or else face “the Penalty of the Law” for aiding him.

Vose made quite an investment in locating and securing Goree. In addition to offering “six Dollars Reward and necessary Charges” for securing him in jail and sending word to Milford, he also ran advertisements in several newspapers. On May 30, his notice appeared in the Boston Evening-Post, the Boston-Gazette, and the Massachusetts Gazette and Boston Post-Boy, all three newspapers published in Boston on Mondays. His advertisement in the Massachusetts Gazette and Boston Post-Boy even included a crude woodcut depicting an enslaved man on the run as a means of drawing attention to it. Apart from the masthead, that was the only image in that issue of the newspaper. The following day, Vose ran the same advertisement in the Essex Gazette, published in Salem. He did not place his advertisement in the Massachusetts Gazette and Boston Weekly News-Letter or the Massachusetts Spy, both published in Boston on Thursdays, perhaps believing that four newspapers printed in two towns provided sufficient dissemination of Goree’s description and the reward for capturing him.

Vose was not alone in placing such advertisements in multiple newspapers. At the same time that he sought to enlist the aid of other colonizers in securing an enslaved youth who liberated himself, Charles Ogilvie ran advertisement about “a Negro Man named MINOS” in the South-Carolina and American General Gazette on May 27, the South-Carolina Gazette on May 30, and the South-Carolina Gazette and Country Journal on May 31. That accounted for every newspaper published in Charleston and the rest of the colony at the time. Ogilvie had recently purchased Minos “at Mr. Benjamin Wigfall’s Sale,” but Minos had other ideas. The enslaver suspected that Minos had assistance from “his Wife at Mr. Elias Wigfall’s” or his “many Relations” in the “Parishes of St. James, Santee, and Christ Church,” believing that they “harboured” or hid him. Although not his purpose in placing the advertisement, Ogilvie revealed one of Minos’s likely motivations for liberating himself.

In both New England and South Carolina, enslavers like Vose and Ogilvie went to great expense in running advertisements about enslaved people who liberated themselves. Such notices were not a feature solely of the newspapers published in southern colonies during the era of the American Revolution. Instead, they appeared in newspapers throughout the colonies, part of the everyday culture of slavery from New England to Georgia.