What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“Sold by the several Post-Riders, and by the Shop-keepers in Town and Country.”

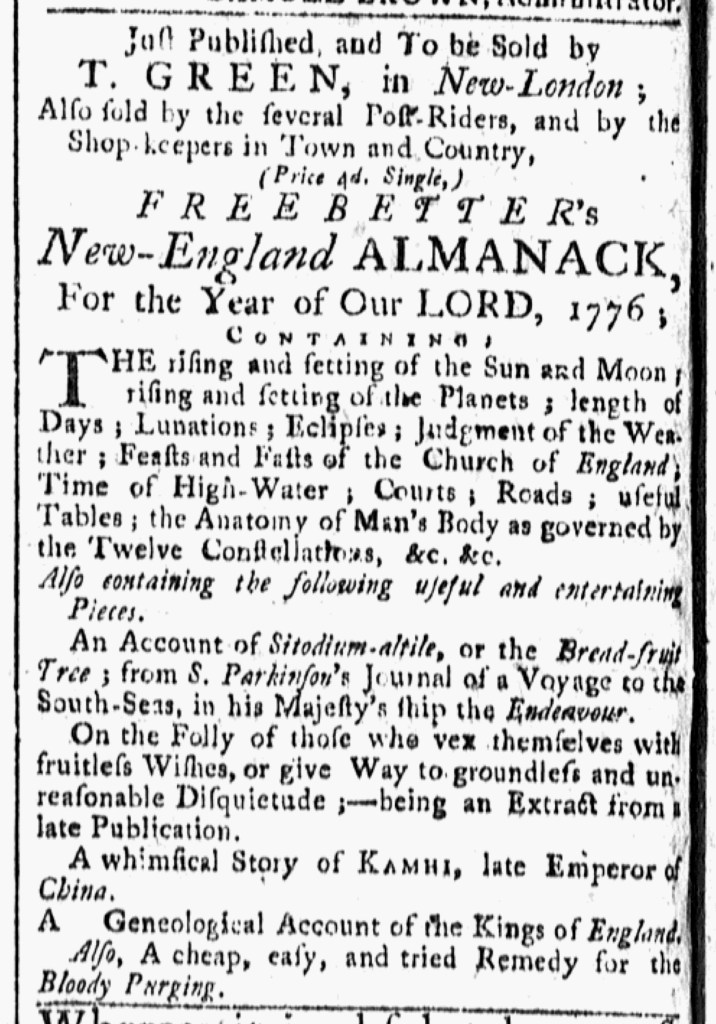

With only a month until the new year began, Timothy Green, the printer of the Connecticut Gazette, advertised “FREEBETTER’s New-England ALMANACK, For the Year of Our LORD, 1776.” He emphasized items that usually appeared in almanacs and called attention to special features. The former included the “rising and setting of the Sun and Moon; rising and setting of the Planets; length of Days; Lunations; Eclipses; Judgment of the Weather; Feasts and Fasts of the Chrich of England; Times of High-Water; Courts; Roads; useful Tables; [and] the Anatomy of Man’s Body as governed by the Twelve Constellations.” The special features included a “whimsical Story of KAHM, late Emperor of China,” and a “Geneological Account of the Kings of England.” They also included an “Account of Sitodium-altile, or the Bread-fruit Tree; from S. Parkinson’s Journal of a Voyage to the South-Seas, in his Majesty’s ship the Endeavour” and an essay on “the Folly of those who vex themselves with fruitless Wishes, or give Way to groundless and unreasonable Disquietude; –being an Extract from a late Publication.” Green may have intended those excerpts as teasers to encourage readers to purchase the original works at his printing office in New London.

To acquire the almanac, however, customers did not have to visit Green or send an order to him. Instead, he advised that “the several Post-Riders” with routes in the region and “the Shop-keepers in Town and Country” also sold “FREEBETTER’s New-England ALMANACK, For … 1776.” The printer established a distribution network for the useful reference manual. Shopkeepers often stocked a variety of almanacs so their customers could choose among popular titles. Printers sometimes offered discount prices for purchasing multiple copies, usually by the dozen or by the hundred. That allowed retailers to charge competitive prices to generate revenue with small markups over what they paid. In this instance, Green did not indicate how much shopkeepers paid for the almanac, only that it sold for “4d. Single” or four pence for one copy. That constrained shopkeepers when it came to marking up prices. In addition to shopkeepers, “several Post-Riders” sold the almanac. That arrangement meant greater convenience for customers and, printers hoped, increased sales and circulation. In the 1770s, printers in New England began mentioning postriders in their advertisements for almanacs and other printed materials, perhaps acknowledging an existing practice or perhaps establishing a new means of engaging with customers. The price that Green listed in his advertisement also kept customers aware of reasonable prices charged by post riders.