What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

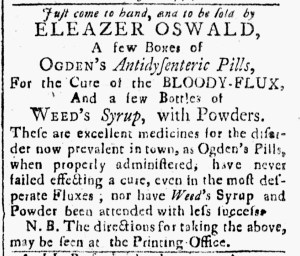

“The directions for taking the above [medicines], may be seen at the Printing Office.”

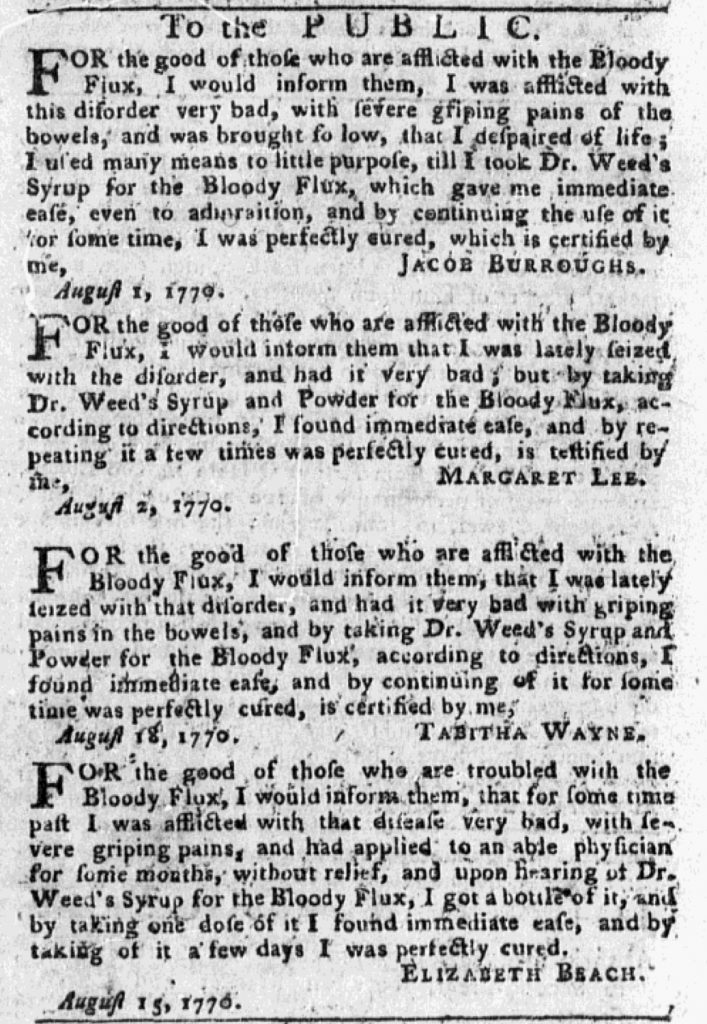

Colonial printers not only disseminated advertisements for patent medicines but also sold them to supplement the revenues from the other goods and services they offered at their printing offices. In some instances, printers cooperated with others in advertising and selling patent medicines. That seems to have been the case with Thomas Green and Samuel Green, printers of the Connecticut Journal and New-Haven Post-Boy, and Eleazer Oswald in the fall of 1774. Oswald advertised a “few Boxes of OGDEN’s Antidysenteric Pills, For the Cure of the BLOODY-FLUX, And a few Bottles of WEED’S Syrup, with Powders” in the October 14 edition of the Connecticut Journal. For those unfamiliar with these nostrums, he explained, “These are excellent medicines for the disorder now prevalent in town, as Ogden’s Pills, when properly administered, have never failed effecting a cure, even in the most desperate Fluxes; nor have Weed’s Syrup and Powder been attended with less success.” As further evidence, Oswald suggested that prospective customers could examine the directions for the patent medicines at the printing office.

Oswald did not mention his affiliation with the Greens, nor did he give a separate address where customers could purchase the medicines. In a town the size of New Haven, local readers did not always need advertisers to list their addresses. In this instance, doing so might have been unnecessary if Oswald worked in the printing office and the community knew that without him stating it in the advertisement. He apparently spent some time in New Haven in addition to seeking opportunities in other towns. Born in England, Oswald migrated to the colonies in the early 1770s. He served as an apprentice to John Holt, the printer of the New-York Journal. In 1779, he entered a partnership with William Goddard in printing the Maryland Journal in Baltimore. In 1782, he established his own newspaper, the Independent Gazetteer, in Philadelphia. In the time between his apprenticeship with Holt and his partnership with Goddard, Oswald formed some sort of relationship with the Greens. He may have worked in their printing office, selling patent medicines as a side hustle, or he may have been a tenant. Either way, his advertisement for Ogden’s pills and Weed’s syrup and powders had the potential to increase traffic in the printing office, making it an even more bustling hub of activity as colonizers exchanged goods and information.