What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“Molasses, Coffee, Chocolate; & all Sorts of Spices.”

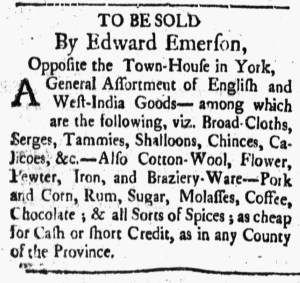

In the summer of 1774, Edward Emerson advertised that he sold a “General Assortment of English and West-India Goods” at his shop “Opposite the Town-House” in York. At the time, his town, about ten miles northeast of Portsmouth, New Hampshire, was in that portion of Massachusetts that eventually became Maine in 1820. When Emerson declared that he set prices “as cheap … as in any County of the Province” in the New-Hampshire Gazette, the local newspaper for York, he left it to readers to decide if he made the comparison to Massachusetts or New Hampshire or both.

Emerson likely considered current events in both colonies important in determining how to present his business in the public prints, making it notable that among the groceries he stocked he listed “Pork and Corn, Rum, Sugar, Molasses, Coffee, Chocolate: & all Sorts of Spices,” but not tea. Merchants and shopkeepers who advertised coffee and chocolate very often promoted tea at the same time, though many had stopped doing so following the Boston Tea Party in December 1773. Emerson had been no stranger to selling tea in the past, including “TEA by the dozen or smaller quantity” along with “Coffee, Chocolate, and all sorts of Spices” in February 1771 and “Bohea TEA, and all sorts of GROCERIES” in July 1772. Yet tea had become a much more problematic commodity in recent months …

… so problematic that that Daniel Fowle, the printer of the New-Hampshire Gazette, devoted the entire front page of the July 8, 1774, edition to reporting on “TWENTY-SEVEN Chests of India TEA … consigned to Mr. Parry” and landed in Portsmouth “before it was in fact generally known that any Tea had arrived in the ship.” The coverage documented the “peaceable and prudent conduct of the inhabitants of Portsmouth” in the face of this crisis, their actions almost certainly influenced by the repercussions that Boston faced following the destruction of the tea there. At a town meeting, “a committee of eleven respectable inhabitants, were elected to treat with the consignee, and to deliberate what would be most expedient to be done in a cause of so much difficulty and intricacy.” They also voted to establish “a watch of twenty-five men … to take care and secure the tea” and prevent disorder and disturbances until the committee could devise a method to remove the tea from Portsmouth. Just as they sought to avoid destroying the tea, they realized that they could not allow any of it to be sold due to “the dependence state of this town and province upon our sister colonies, even for necessary supplies, which would undoubtedly and justly be denied” should they “suffer the sale and consumption of said Tea.” Once the tea had been safely sent away, the town meeting voted to create “a committee of Inspection to examine and find out if any Tea is imported here” and another committee to draft a measure “against the importation, use, consumption or sale of all Teas, in this town while the same are subject to a duty.”

Given the circumstances, Emerson made a savvy decision not to market tea in his advertisement in the New-Hampshire Gazette. Not all merchants and shopkeepers refrained from advertising and selling tea at the time, but many decided to discontinue trading that commodity even before boycotts officially went into effect.