What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“He will sell … at so cheap as Rate as he doubts not will give Satisfaction to every Purchaser.”

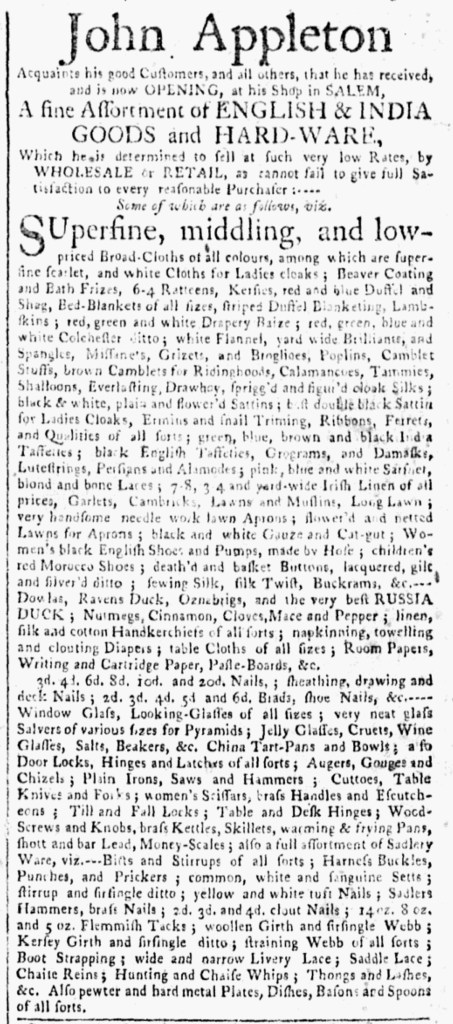

George Deblois regularly advertised in the Essex Gazette. On February 15, 1774, he placed a lengthy notice to promote a “fine Assortment of ENGLISH and HARD-WARE GOODS” that he “just received … from LONDON.” He asserted that these items were “Suitable for the approaching Season,” encouraging consumers to purchase in advance or at least keep his shop in Salem in mind when they were ready to shop for in the coming weeks and months. A catalog of his merchandise, divided into two paragraphs, accounted for most of the advertisement. The first paragraph listed the “ENGLISH” goods, mostly textiles and accessories. Deblois stocked “Scotch Plaids,” “Devonshire Kersies,” “stampt linen Handkerchiefs,” “a fine assortment of men’s worsted Stockings,” and “Hatter’s Trimmings of all sorts.” He devoted the other paragraph to housewares and hardware, including the “best of London pewter Dishes,” “hardmetal Tea-Pots,” “steel and iron plate Saws of all sorts and sizes,” and “Brads, Tacks and Nails of all sorts.”

The merchant concluded his advertisement with two common appeals, one about consumer choice and the other about his prices. The lengthy lists of goods already demonstrated the many choices available to his customers, but he insisted that he also stocked “a great Variety of other Articles, too tedious to enumerate in an Advertisement.” Readers would have to visit his store to discover what else they might want or need that happened to be on his shelves. No matter what they selected, his customers could depend on paying low prices. Deblois declared that “he will sell by Wholesale and Retail … at so cheap a Rate as he doubts not will give Satisfaction to every Purchaser.” Other advertisers frequently made a nod to low prices. Elsewhere in the same issue of the Essex Gazette, for instance, John Appleton offered his wares “very cheap.” Deblois embellished his appeal about prices, hoping to draw the attention of prospective customers and convince them that he offered the best deals. They would depart his store not only pleased with the goods they acquired but also with a sense of “Satisfaction” about how much they paid. Deblois encouraged consumers to visit his shop by setting favorable expectations for their shopping experiences.