What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

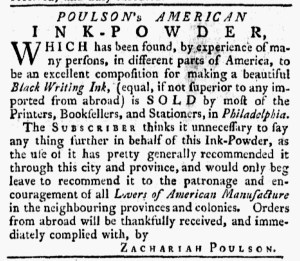

“POULSON’s AMERICAN INK-POWDER.”

Just four days after Benjamin Towne launched the Pennsylvania Evening Post, James Humphreys, Jr., commenced publication of the Pennsylvania Ledger on January 28, 1775. In less than a week, the number of English-language newspapers printed in Philadelphia increased from three to five, rivaling the number that came off the presses in Boston. No other city in the colonies had as many newspapers. Humphreys incorporated the colophon into the masthead, advising that he ran his printing office “in Front-street, at the Corner of Black-horse Alley:– Where Essays, Articles of News, Advertisements, &c. are gratefully received and impartially inserted.”

Unlike the first issue of the Pennsylvania Evening Post, the inaugural edition of the Pennsylvania Ledger carried advertisements. Humphreys placed some of them, one hawking “POLITICAL PAMPHLETS … on Both Sides of the Question,” another promoting an assortment of books he sold, and a final one seeking “an APPRENTICE to the Printing Business.” Nine other advertisers placed notices, all of them for consumer goods and services. They took a chance that the new newspaper had sufficient circulation to merit their investment in advertising in its pages.

Among those advertisers, Zachariah Poulson marketed “POULSON’s AMERICAN INK-POWDER.” He asserted that “most of the Printers, Bookseller, and Stationers, in Philadelphia” stocked that product. Customers just needed to request it. With the deteriorating political situation in mind, especially the boycott of imported goods outlined in the Continental Association, Poulson called on “all Lovers of American Manufacture” in Pennsylvania and “in the neighbouring provinces and colonies” to choose his ink powder over any other.

Edward Pole inserted the lengthiest advertisement (except for Humphreys’s notice cataloging the books he sold). It filled half a column, the first portion devoted to the merchandise available “at his GROCERY STORE, in Market-street” and the rest to “FISHING TACKLE of all sorts,” “FISHING RODS of various sorts and sizes,” and other fishing equipment. In advertisements in several newspapers published in Philadelphia (and, later, with ornate trade cards that he distributed), Pole regularly marketed himself as a sporting goods retailer. For the first issue of the Pennsylvania Ledger, he adorned his advertisement with a woodcut depicting a fish that previously appeared in his notices in Dunlap’s Pennsylvania Packetin May and June 1774.

Humphreys provided residents of Philadelphia and other towns greater access to news and editorials with the Pennsylvania Ledger, but that was not all. The publication of yet another newspaper in Philadelphia increased the circulation of advertising in the city and region, disseminating messages to consumers far and wide. Not long after Humphreys published that first issue, advertisers took to the pages of the Pennsylvania Ledger to publish notices for a variety of purposes, supplementing the information the editor selected for inclusion.