GUEST CURATOR: Patrick Keane

What was advertised in a colonial newspaper 250 years ago today?

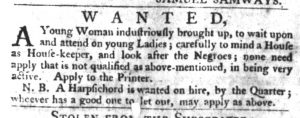

“WANTED: A Young Woman industriously brought up … carefully to mind a House.”

I liked this advertisement, especially after curating the Slavery Adverts 250 Project, as this has to do with slavery. However, the advertisement did not talk directly about the slaves. Instead, the advertiser was looking for a woman willing to work in the house and watch the master’s slaves. Only women skilled enough to do the job were asked to apply for it: “none need apply that is not qualified as above-mentioned.” The advertiser specifically wanted a woman because during the colonial period woman were expected to do the housework.

One summary of Ruth Cowan Schwartz’s More Work For Mother: The Ironies of Household Technology from the Open Hearth to the Microwave, explains that a “division of labor kept a man and a woman together or joined them in a household in some way.” Other than watching the slaves, the woman in this advertisement would do all of the housework as well, including kitchen work, cooking, cleaning, and taking care of children.

**********

ADDITIONAL COMMENTARY: Carl Robert Keyes

This employment advertisement simultaneously offers a wealth of details concerning domestic life in one South Carolina household and provides frustratingly few specifics. As Patrick indicates, the advertiser sought a young woman who would be responsible for all sorts of housework as well as overseeing slaves. In addition, the young woman was expected to be a servant to an unspecified number of “young Ladies.”

This advertisement reveals quite a bit about women’s responsibilities in early American households. Given traditional gendered divisions of domestic labor that have continued to the present, it comes as little surprise that an eighteenth-century employment advertisement positioned housework as women’s domain. Looking after a house, however, included more than cooking and cleaning, especially in a household with servants or slaves. The work of a housekeeper also included household management intended to keep everything running smoothly.

Who were “the Negroes” mentioned in this advertisement? How many slaves lived and worked in this household? What were their responsibilities? How much of the domestic labor did they perform? Was the successful applicant expected to do any cooking or cleaning herself? Or was she an overseer within the household, someone who delegated tasks and confirmed they were completed?

The advertisement also reveals little about the family that wanted to hire a young woman to join their household. Apparently it was a family of some affluence. Not only did they own slaves and intended to hire a servant, they also, according to a nota bene appended to the advertisement, wished to lease (but not buy) a harpsichord. Perhaps the young ladies of the house took lessons and entertained guests as a means of demonstrating their manners and refinement.

Despite the various details about the prospective housekeeper’s responsibilities, the advertisement does not indicate whether a mistress of the household was present. Did a wife and mother reside in this household? Did the family seek to demonstrate their wealth and status by hiring a servant to take on the tasks that the mistress of the household would have pursued in other homes? Or was the wife and mother deceased or otherwise absent, making it imperative to bring in an outsider to assume those responsibilities?

Answering those questions required applicants to “Apply to the Printer.” Unfortunately, that is not an option for modern readers. I appreciate how Patrick used this advertisement to explore women’s work in colonial America, but I remain puzzled about some of the household dynamics raised in this particular employment notice.