What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

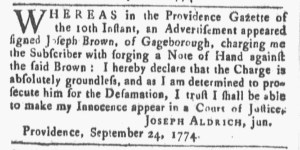

“I am determined to prosecute him for the Defamation.”

Defamation! That was the defense Joseph Aldrich, Jr., made against allegations that appeared in the September 10, 1774, edition of the Providence Gazette. The original accusation and Aldrich’s response both ran as advertisements. It started with one that read, “I JOSEPH BROWN, of Gageborough, in the County of Berkshire, and Province of the Massachusetts-Bay, give this public Notice, that Joseph Aldrich, jun. of Gloucester, in the County of Providence, hath forged or counterfeited a Note of Hand against me the said Joseph Brown, for Ninety odd Pounds Lawful Money.” The notice offered a warning: “All Persons are therefore cautioned against taking any Assignment of said Note, as I am determined to prosecute for the Forgery, instead of paying the Contents.”

Aldrich apparently did not become aware of what Brown charged right away since he did not respond in the next issue of Providence Gazette, but not much time passed before he either read Brown’s advertisement or someone told him about it. That spurred the aggrieved Aldrich into action. He placed his own advertisement that cited the notice “charging me the Subscriber with forging a Note of Hand against the said Brown” and asserting that “the Charge is absolutely groundless.” Just as Brown stated that he intended to take the matter to court, so did Aldrich. “I am determined to prosecute him for the Defamation,” he declared, confident that “I shall be able to make my Innocence appear in a Court of Justice.”

Yet it was not a “Court of Justice” that mattered immediately; it was the court of public opinion that Aldrich sought to sway. Brown had damaged his reputation, perhaps imperiling his ability to conduct business and support his family. For Aldrich, the most important news in the September 10 edition of the Providence Gazette appeared among the advertisements, not among the articles and editorials that so animated readers as the imperial crisis intensified. Paying to run a notice gave Brown access to the public prints to share his version of events involving the supposedly forged and counterfeit note. In turn, taking out his own notice allowed Aldrich to defend himself against that calumny. In both instances, advertisements doubled as local news.