What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago this week?

“He therefore hopes for the countenance of those who wish to encourage their own manufactures.”

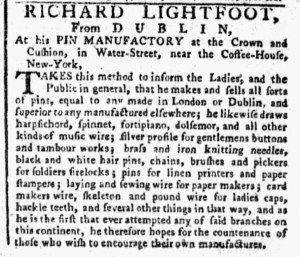

In the summer of 1775, Richard Lightfoot placed a newspaper advertisement to promote his “PIN MANUFACTORY at the Crown and Cushion” in New York. In addition to “all sorts of pins,” he also produced a variety of other wirework, including “harpsichord, spinnet, fortepiano, dolsemor, and all other kinds of music wire,” “brass and iron knitting needles,” “pins for linen printers and paper stampers,” and “laying and sewing wire for paper makers.”

Lightfoot addressed “the Ladies,” who presumably constituted a significant portion of his customers, yet also directed his advertisement to “the Public in general.” After all, he had an interest in the entire community knowing about the work undertaken at his “PIN MANUFACTORY” and his contributions to the American cause through his participation in the marketplace. Lightfoot proclaimed that “he is the first that ever attempted any of said branches,” the production of the various kinds of wirework, “on this continent.” He did so at a time that colonizers observed the Continental Association, a nonimportation agreement devised by the First Continental Congress in response to the Coercive Acts. That pact called for encouraging “Industry” and “the Manufactures of this Country” as alternatives to imported goods. Under those circumstances, Lightfoot hoped “for the countenance of those who wish to encourage their own manufactures.” That meant that “the Public in general” should support his enterprise by recommending it to “the Ladies” who purchased and used the pins and other items he made.

When they did so, they could depend on the quality of those products. Lightfoot asserted that his pins were “equal to any made in London or Dublin, and superior to any manufactured elsewhere.” He was qualified to make that claim, indicating that he was “From DUBLIN” and likely learned and practiced his trade there before migrating to New York. Claiming that authority, Lightfoot assured prospective customers that they did not sacrifice quality when they applied their political principles to their decisions about which pins to purchase. It did not matter that the Continental Association prohibited buying imported pins because Lightfoot made and sold pins that were just as good as (or even better than) pins produced elsewhere!